As production becomes increasingly globalised, businesses need to consider how they would be aff ected if their suppliers or their suppliers’ suppliers fail to deliver.

The Japanese earthquake, tsunami and associated power and infrastructure problems were a wake-up call for Western companies about the need to manage supply chain risks. Wherever you source your products and components from, you need to protect your business against disruption of supplies. Your organisation almost certainly has business interruption insurance – probably linked to a property damage policy – which would protect you in the event of a fire or other disaster. But it is not just an incident at your own premises that can halt your activities.

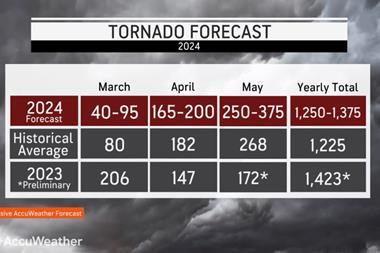

Would your business be able to continue functioning successfully if one of your key suppliers was put out of action? It is possible to extend your business interruption cover to include disruption from damage to your suppliers’ premises. At one time, insurers were prepared to provide this for unspecified suppliers. Now, they are more likely to require details of any suppliers added to your policy. This allows them to identify suppliers in areas where there may be a high risk of natural catastrophes, such as earthquakes and tornadoes, to avoid too much exposure to certain areas.

As it did in Japan earlier this year, a natural disaster can affect vital infrastructure, such as transport links. The ensuing damage to nuclear installations after the earthquake and tsunami necessitated power cuts. Both these factors affected companies outside the immediate earthquake and tsunami damage zone – and led to disruptions in supplies to the West.

It is not only physical damage that could affect your suppliers’ ability to deliver. Volatile political situations and civil unrest can also prevent companies from functioning normally and shipping goods out of their country. In addition, regulatory authorities in the supplier’s country may close a plant if it is considered unsafe or fails to meet required standards. There is also the danger that your supplier might experience financial problems or go bust.

For these reasons, some insurers offer contingent business interruption insurance for your supply chain risks, which can be triggered by a wider number of events than just physical damage. A basic rule of thumb is that anything that might stop your business functioning successfully could affect a supplier – with the added risk of a natural catastrophe if the supplier is located in a high-risk area.

Going beyond insurance

Insurance is valuable, but managing your middle market company’s supply chain risk involves more than just buying cover and hoping for the best. The challenges can be particularly great if your business buys goods and components from suppliers in the developing world. You may have made an initial visit to survey facilities and physical protection measures as well as to agree quality and delivery times, and then incorporated the appropriate provisions into the supply contract. But after that you may have to take quite a lot on trust.

If, for example, a natural catastrophe occurs or the supplier gets into financial difficulties, it may underplay any problems because it does not want to risk losing your business. It is difficult to know what is going on if a supplier is not on your doorstep.

Your risk of disruption is also greater if you minimise the amount of stock you hold, relying on ‘just in time’ delivery to meet your contractual obligations to your customers. They may be doing exactly the same, relying on deliveries from you. If this is the case, there will not be a cushion of products for either of you to fall back on, should a vital link in your supply chain break.

Looking into the chain

The first rule for managing your supply chain risk has to be: understand its components and any interdependencies. The longer the supply chain, the more difficult this can be. But even companies producing components and goods in-house cannot be complacent, because they will rely on some raw materials supplied from outside. Moreover, bottlenecks can occur with in-house, as well as external, production. You need to examine your first tier of suppliers. The questions you should ask are:

- Are they based in a politically stable country?

- Does that country have a history of natural catastrophes?

- Are the suppliers financially robust?

- Could you replace them quickly and cost effectively if there was a problem?

- Would you get priority for deliveries if a supplier had a problem that restricted production?

If you are producing goods internally, hopefully only the fourth question will apply. You need to consider whether there is an essential production unit on a site that supplies various parts of your organisation. What happens if there is a major fire? Question five needs particular thought.

Putting aside any assurances that you may have received from the supplier concerned, it will inevitably look after its biggest customer – and that may not be you. It is always worth asking an important supplier who else they deal with, so you can gauge just how much sway you have with them.

Rely on no one

It is also important not to take too much comfort from the existence of other suppliers that you hope can step in if your appointed supplier cannot deliver. The problem could be in your supplier’s own supply chain – they could be relying upon a small business, which is also supplying their competitors. If that business goes down, there could be major repercussions for everyone.

As such, if you are sourcing specialist goods or components, it may be worth investigating beyond your tier-one suppliers to find out if they have sources they can call upon if there’s a problem. If you do have a vital supplier in your chain that could cause major problems if it fails to deliver, you need to do some contingency planning. Consider getting other suppliers lined up to fill any gap.

These might also be the first port of call for your competitors if they have problems, so you might have to encourage their loyalty. Splitting your production arrangements between suppliers might minimise your bulk purchase discounts, but could serve you well if one has a problem.

Managing your supply chain risk involves more than just

buying cover and hoping for the best. The challenges can be

particularly great if you buy goods from suppliers in the developing world

Asking a company that you have not dealt with before to help you out when you have a problem could be difficult if larger competitors are also asking and already have a relationship with them.

Remember, too, that the production of some components tends to be concentrated in particular regions. When the Japan disaster occurred, for example, automotive and electronic companies were the worst hit because the country was an important source of their components. If you have two main suppliers, it would be sensible to ensure that these are not based in the same region, so they would not both be affected by a national natural catastrophe.

If a link in your supply chain fails and if you have to source goods elsewhere at a greater cost, you may be able to recover this additional expenditure. Your business interruption insurance may cover increased cost of working – the money you have to spend to mitigate your total loss.

No comments yet