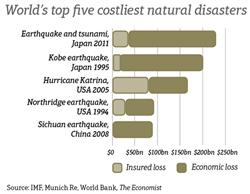

The Japanese earthquake and tsunami illustrated the complex nature of global supply chains, and how businesses can be brought to a standstill by events a long way down the line. Risk managers need to know where their exposure lies

“There’s a changing risk landscape. Many companies are part of a vast, interdependent global supply network and some do not even manufacture themselves, but buy everything in. The natural catastrophes of 2011 and their effect on business continuity have brought that more into focus.” So says FM Global vice-president, market and business development, Martin Fessey.

Fessey believes that the events of this year have reinforced the importance of insurance as a business continuity tool, something that may have been forgotten in less hazardous times. “There are a number of estimates as to the total insurance bill for damage so far this year. While they vary, depending on the source, they have one thing in common – they are all high. The considerable amount of money that has been paid by the insurance industry has helped companies to preserve their cash flow, and to get back into operation as soon as possible,” he says.

“There has been some criticism of supply chain products in the past few years, suggesting that they may not cope with the needs and expectations of companies. But experience this year clearly highlights the importance of property and business continuity insurance,” Fessey adds.

Another lesson that has been illustrated by recent events is that many businesses’ strategies have introduced new exposures. “They may not have fully recognised this or understood all the implications,” Fessey says.

“Much of the interruption that has occurred, certainly in the case of Japan, has not necessarily involved high-profile lines of manufacturing but relatively low-profile, although perhaps high-value, items that are critical in getting products out of the door.”

Reportedly, Japan produces around 40% of the world’s technology components including chips, memory for digital phones, cameras and PCs, glass for flat screens, capacitors and transistors. Many of its customers are well-established brand names in Europe, and the components concerned are crucial for their products.

FM Global vice-president of operations and engineering manager Tom Roche says that it is not uncommon for companies to choose the same suppliers or for manufacturers in particular regions to supply a number of companies in the same industry sector. “The development of large specialist suppliers in such regions means that they can offer the advantages of good-quality control and competitive pricing. It also means that an event in one region can cause many ripples with, in some cases, devastating effect,” he explains.

Willis practice leader for life sciences and supply chain Tom Teixeira comments: “Before the disasters that happened this year, a lot of risk managers would have considered that they were covered for contingent business interruption by the extensions of their property and business continuity policies. However, in some cases these extensions did not provide enough cover. And, in any event, some of the supplier disruption was not down to property damage – as was the case, for example, in respect of the production interruptions caused by the power blackouts in Japan.”

He recommends: “Companies should look at interruption as a whole, taking account of the fact that it can be caused by a number of different risks such as terrorism and financial fragility.”

Signs of a step change

Teixeira also notes that some companies that were thought to be good at managing their complex supply chains, particularly in the automotive sector, proved not to know who their critical suppliers were or understand the scale of business interruption that they could be faced with.

Teixeira says: “There needs to be a step change, and we’re starting to see signs of it. Risk managers are now looking to their advisers for assessment of their internal facilities, how these integrate with tier one of their supply chain, what their crucial supplies are and where their exposure lies.”

“Once they better understand their critical supplies and level of exposures,” he adds, “it’s possible to come up with some risk management solutions.”

In some cases, this could be insurance, particularly for smaller companies that do not have the resources, capital or know-how to protect themselves. Larger companies may want to reassess their stock level strategy – ‘just in time’ may be not be appropriate for them. If they have identified a critical supplier or process, they might consider it worth spending extra money to dual source or consider holding buffer stocks.

Teixeira adds: “Companies may have a good understanding of their tier-one suppliers – but what’s really happening behind this level in tiers two, three, four, and so on? It will be critical to come up with methodologies and processes to understand all parts of the supply chain.”

He warns that getting risk management strategies right up front is critical: “In some industries, such as aerospace and pharmaceuticals, if you lose a supplier overnight you cannot just switch to someone else to supply the product. It can take six to eight months to get another supplier approved by the regulatory body. That’s a lot of business interruption.”

Having to make an emergency decision on switching suppliers presents other dangers, too. Many large European companies are careful to take corporate governance and social responsibility issues into account when selecting suppliers. They also check on regulatory compliance.

The need to get a new supplier on stream immediately may not allow time to vet them as carefully, and that could create reputational problems. In addition, time pressures mean that companies may not be in a good negotiating position so could end up paying their replacement supplier considerably more, which will affect their profit margins.

Miller Insurance Services’ head of property – corporate risks, Trevor Young, agrees that the 2011 natural catastrophes have tested the resilience of business continuity plans and in particular dual sourcing arrangements.

It takes two

“A company may have dual-sourcing arrangements with two suppliers, perhaps getting 80% of its product from one and 20% from the other – but it needs to make sure that either one has the ability to pick up the shortfall as much as possible should the other fail,” Young explains. He stresses that business continuity plans and the contractual arrangements around them should be as flexible as possible to mitigate any potential loss.

He adds that the insurance market will be scrutinising the extent of information and coverage provided for suppliers and customers. “Some insurers are still providing unnamed coverage, not just for first-tier suppliers but also for those in the second and third tiers. The market will be looking to tighten up its information requirements considerably. Any open coverage provided will be severely limited. Risk managers must provide more data or expect more limited cover in the future.”

Young points to the contradiction between business imperatives and continuity protection. Businesses are looking to reduce their suppliers to gain better purchase terms, but this relinquishes the continuity resilience that is provided by having a large number of suppliers.

Some of the shortfall associated with a multi-supplier strategy may be made up in reduced insurance premiums. Young cites the example of a retailer sourcing from hundreds of suppliers. “From the procurement point of view, the approach looks unwieldy and not very effective but insurers were prepared to give preferential rates.”

“Risk managers seem to have been shocked by a number of bottlenecks in their supply chains,” Young adds. “Despite good governance, there still remain areas where companies are completely reliant on deliveries from one supplier of certain parts in a process – or even the machinery they use to make their products.”

A welcome test

Not all the lessons are negative. Fessey says that many companies have managed their continuity problems unexpectedly well.

“A message that we’re hearing from some clients is that, although their business continuity plans may not have gone absolutely according to plan, everyone in the company worked well together to deliver on business continuity. The situation clearly brought out strengths in companies’ ability to manage ‘on the run’ and focus on the key issues. This reinforces the belief that risk management is a key part of general management.”

Fessey says that Global FM has seen a number of examples where potentially significant business interruption has been reduced because of good management. “Perhaps insurance payments helped here too, because they reduced the criticality of replacement supplier prices, enabling businesses to focus on quality, specifications, delivery times and so on,” he adds.

Roche concludes that companies have drawn several important lessons from this year’s catastrophe events. “[They] have learnt quite a lot about their businesses in terms of where some of their products actually come from. It’s been a call to arms for risk managers to reach out in their organisations and assist in this area.”

It has also been an eye-opener for some businesses to learn just how important they are to their suppliers. “In some cases,” Roche adds, “they discovered that they were not a major customer and their negotiating power was less than they had anticipated.” SR

Key lessons

- Insurance continues to be a valuable business continuity tool.

- The implications of business strategies such as ‘just in time’ deliveries need to be weighed against potentially increased loss exposure.

- Regional concentrations of suppliers of similar goods exacerbate shortages in the event of natural catastrophes.

- Companies need to better understand their supply chains behind their tier-one suppliers.

- Dual sourcing or buffer stocks may help to

mitigate loss.

- Switching suppliers quickly in an emergency can be expensive and may raise corporate governance or regulatory issues.

- Insurers may want more information on companies’ supply chains or limit cover for unspecified suppliers.

- Good risk management - and good management generally - has helped some businesses to reduce disruption and their potential loss.