Interstate violence with regional consequences is now the most likely of all global risks, according to the World Economic Forum

When Shell was forced out of Ogoniland, Nigeria, in the mid 1990s after years of oil spills, nobody foresaw the chain of increasingly dire consequences that remains unresolved to this day.

First, contamination from the spills – most of which Shell blamed on sabotage of pipelines by lawless locals – destroyed the way of life of a large number of the Ogoni people as it affected the quality of air and water across whole areas of the Niger delta. It also destroyed much of the fish life as oil seeped into rivers.

Within a few years of the departure of Shell and other oil majors, the Ogoni, who have lived in the region for 500 years, organised widespread protests that have led to more than 20 years of sporadic violence between neighbouring tribes and government forces. Meanwhile, abandoned pipelines continue to be sabotaged, causing further environmental destruction.

For years the Nigerian government, anxious to resume production in the oil-rich region, was accused of sending in police to brutalise Ogoni protesters, many of whom were arrested without charge. Some were executed. By unofficial estimates, 2,000 Ogoni have been killed and 1,000 more have fled the state, triggering further conflict with neighbouring tribes.

Taking the fatal chain of events into account, the United Nations Environmental Programme has labelled the contamination and its long-running results as one of the worst examples of environmental neglect in sub-Saharan Africa.

Last year UNEP released a damning report of the physical damage after a spending 14 months in the area.

“UNEP’s field observations and scientific investigations found that oil contamination in Ogoniland is widespread and severely impacting many components of the environment,” the report said.

“Even though the oil industry is no longer active in Ogoniland, oil spills continue to occur with alarming regularity. The Ogoni people live with this pollution every day.”

Alarmingly crude oil is still being illegally distilled for profit in makeshift facilities and UNEP concludes that this continues to cause pockets of environmental devastation in the region.

In the report’s scathing conclusion, UNEP wrote: “The extensive oil contamination in the Niger Delta is one of the principal drivers of ongoing social unrest and violence.”

That assessment supports the findings of the World Economic Forum that interstate conflict with regional consequences is now rated as the most likely of all global risks, with water crises highest in terms of impact.

Violence

It is ongoing situations, such as in Ogoniland, that has prompted the UN to turn more of its attention to resource-based tensions.

Since the turn of the millennium, the UN has come to recognise that environmental disasters can lead to conflicts over natural resources that become culturally embedded and difficult to resolve.

“Social conflicts over the ownership, access and use of natural resources are frequent”, UNEP said in a report in 2015. Although their resolution can be managed in a way that breaks down tensions, the UN acknowledges that such conflicts can all too readily end up in violence.

“Weak institutions, fragile political systems and divisive social relations can be drawn into downward cycles of mistrust, marginalisation, conflict and aggression,” UNEP says. And although tensions and grievances over natural resources are rarely the sole cause of violent conflict, they often provide the spark that triggers a whole chain of multi-dimensional events that are rapidly politicised. Indeed there are ongoing, resource-based conflicts in Uganda, Burundi and Rwanda.

It is because of these that the UN has pushed environmental and resource issues up the agenda. “Resolving natural resource conflicts is a defining peace and security challenge of the 21st century,” UNEP says.

“The geopolitical stakes are high as the survival, or authority, of states may depend on securing access to key natural resources.”

These hotspots are also found in Asia, but the majority are simmering away in sub-Saharan Africa. In the volatile Democratic Republic of Congo, for instance, illegal exploitation of natural resources by local militia and international criminal networks has been a source of tension in widespread communities for many years. In addition, the governments of Haiti and the Dominican Republic, have been at loggerheads for years over a degraded environment resulting from depletion of resources along their border

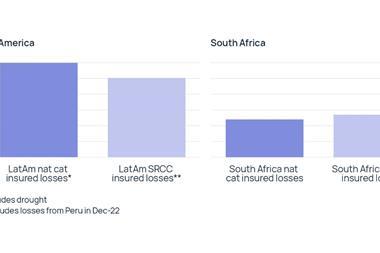

As the authority on the subject, UNEP has identified the main linkages between environmental degradation or resource-based disputes and violence. The organisation found that water, land, extractives and renewables in varying degrees are the main factors contributing to long-running tensions that ended up in armed conflict in 60 countries in the last 25 years. Of these, land is the main source of dispute, especially during the actual fighting but also during the peace negotiations.

However, all four elements rank highly as the cause of resentment. For instance, land, extractives, renewables and access to clean water were major issues before, during and after the conflict. In peace negotiations the warring parties typically struggle to agree on how to divide up these quality-of-life issues as they vie to protect their future.

Flashpoint

Extractives remain a particular flashpoint, as the Ogoniland disaster shows. UNEP, which is deeply involved in achieving diplomatic solutions in these conflicts, identifies a clear chain reaction starting with a lack of proper consultation with the local community.

Then in the event of environmental problems, the lack of a properly managed grievance mechanism or the unavailability of adequate compensation often leads to tensions, particularly when security forces are sent in. But even if there are no environmental problems, with so much money on the table there is often skimming or wholesale corruption in the absence of a reliable monitoring process. If the local community do not see tangible benefits, they become resentful. And the final nail in the coffin occurs if the government fails to use the revenues to address public priorities that were agreed beforehand.

Meanwhile, the problems in Ogoniland may finally be resolved, largely through the intervention of UNEP. Nigeria’s new president, Muhammadu Buhari, has promised a corruption-proof system for administering the $1bn compensation fund agreed by Shell and other parties.

Environmental experts say it will take up to 30 years to clean up the region.

No comments yet