As the debt crisis worsens, Portugal and Ireland are struggling to regain their composure and Greece is in line for yet another bail-out. What will happen if the trouble spreads?

The escalating eurozone debt crisis could have a big impact on European insurers and, if it does, it could put upward pressure on premium rates.

Considerable uncertainty in the global economy, stock market volatility and talk of a double-dip recession has been a feature of the past year. At the time of writing, emergency meetings were taking place to approve a further €109bn for Greece after a €110bn bail-out a year ago.

The failure to deal decisively with Greece has eroded confidence and made a default on its debts seem all the more likely. In the rest of Europe, there are fears that the debt crisis that began with Greece, Portugal and Ireland could spark contagion to some of Europe’s bigger economies, in particular Italy and Spain.

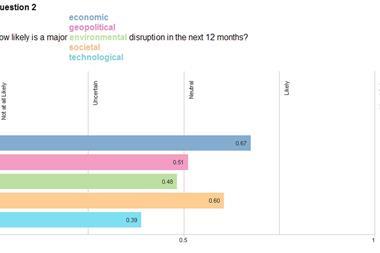

For the risk management community the macro-economy is a concern: it holds the more immediate prospect of premium rate increases in the insurance industry as a result of sovereign debt exposures that threaten businesses going forward. This was one of the key messages ahead of the Ferma conference in early October.

View from Ferma

“We have a very difficult economic environment and the sovereign debt crisis will be of concern to risk managers as it is to us,” said Willis Group Holdings’ continental Europe operations chief executive, Adam Garrard. “The European Central Bank estimates that 17% of insurer assets are tied up in Portugal, Spain, Italy and Greece.

“Obviously if we have a sovereign debt failure, that will impact on insurers’ ability to write at a price that risk managers will be comfortable with,” he continued. “We also have the issue of inflation. So if we have a joint issue with inflation and sovereign debt default, I think that all bets will be off and (re)insurance pricing will certainly rise.”

Beyond the cost of insurance, there were mixed reactions from Ferma delegates to the debt crisis. It was not as dominant a topic at the conference as many had anticipated.

There is a feeling that the eurozone problems are more an issue for banks, which the European Central Bank (ECB) has promised to bail out should they risk failure. It will step in and buy up to €40bn in covered bonds to make borrowing easier should the crisis escalate.

As the economies of the west stagnate and inch closer towards a second recession, it is clear there are no quick and easy solutions and there will be slow growth for years to come. This was the view of Deutsche Bank chairman Dr Josef Ackermann, who presented the keynote speech.

“Many still think of the debt crisis as a short-term phenomenon, linked to the financial crisis,” he said. “However, it is more accurate to see it at least as a medium-term problem. Many have lived beyond their means for years, if not decades. The ageing of societies - with the ensuing consequences in terms of higher public spending on pensions and healthcare - will only compound the debt problem.”

Many at Ferma felt this bleak economic outlook contradicts day-to-day business activities, with order books filling up and ongoing demand for risk management expertise. “At the end of the day it’s a self-fulfilling prophecy,” said president of IFRIMA Carl Leeman, speaking at Ferma. “If the politicians and the banking sector continue to tell us that things will go badly, then they will go badly and people will not spend anymore.

“Although the economic outlook according to our friends in the financial industry is not very bright, I think the future for risk management is very bright because there will be more and more need of risk managers, for experienced staff and people with fresh ideas.”

Insurance representatives were quick to allay fears they would be unduly negatively impaired by the crisis, pointing out that they have spent the last 18 months de-risking their investment portfolios to reduce exposure to eurozone debt. With this corrective action, capital should not be overly impaired in the event of a default to the extent that the cost of insurance would need to go up.

Rating agency view

Fitch Ratings does not anticipate widespread insurance rating downgrades as a result of the debt crisis, unless it spreads and becomes systemic. The rating agency cut Italy’s sovereign credit rating by one notch (to A+) and Spain’s by two (to AA-) on 7 October, keeping both countries on negative outlook, suggesting there may be further downgrades in the future.

At the moment, a Greek default or other ‘peripheral’ defaults might impact insurers operating in those countries, but it is unlikely to be felt across Europe, according to Fitch. This view is based on a number of assumptions, including the ultimate survival of the eurozone and regulatory forbearance.

“We are not expecting widespread rating changes on the back of a hypothetical Greek, Portuguese or Irish default, but if Italy or Spain were to default I’d expect quite significant negative rating actions,” says Fitch managing director and head of EMEA insurance Chris Waterman. “But ultimately I would expect that governments would step in to prevent the default of systemically important banks and sovereigns.

“If we see contagion I would expect that it will materially impact insurance companies’ profitability and also capital,” he continues. “When capital starts being eroded, management don’t have too many levers that they can pull. That would be the key time when they would likely increase premium rates to support earnings and generate capital.”

While a Greek default is more likely under Fitch’s current set of assumptions, there are several mitigating factors helping the insurance industry withstand such an event. Waterman confirms there has been widespread de-risking of balance sheets in the industry, particularly for insurers with cross-border exposures.

Regulatory action should also shield insurers if there is a Greek default. In Italy, for instance, the regulator is not requiring insurers to report unrealised losses on Italian sovereign debt. And insurance balance sheets are stronger than they were before the Lehman Brothers collapse in 2008, having seen a significant increase in shareholders’ equity over the past three years.

Nevertheless, capital in the industry has been put under pressure in 2011, with a record $70bn of catastrophe losses in the first half of the year. The low interest rate environment means investment returns are low and reserve releases are becoming more difficult.

New catastrophe model releases and anticipation of the Solvency II framework in Europe are also driving up capital requirements for some insurers. Solvency II has also put insurers under pressure to increase their holdings of sovereign bonds.

“I think things could potentially move quite quickly,” says Waterman. “There are a number of factors impacting negatively on earnings, but at the end of the day it depends on how they all play out and whether capital is taken out of the market in sufficient volume to result in premium rate increases.”

“Our analysis of insurance company balance sheets indicates that there has been some de-risking to peripheral eurozone countries and that exposure to Greece, Portugal and Ireland on average across the industry is low,” he continues.

“It’s really Italy and Spain that are much more significant and while we view default of these countries as highly unlikely, given their relatively strong credit ratings, if that were to occur we would expect to see substantial capital erosion. That may ultimately impact the need to increase rates, among other things.”

No comments yet