Despite global misery, economies in Asia remain strong, making it attractive for new business. But with this come new considerations for risk managers who must rethink their strategies if they are to approach this area

Bucking a gloomy global trend, Asian economies are booming. Even when the threat of slowdown is discussed, it is done so in terms of growth figures that make managers and politicians in Washington, Berlin and London blush.

The regional titans, India and China, are being driven forward by exports developed and marketed by an ambitious new middle class, which is in turn creating a buoyant domestic market for consumer goods and services.

Upstart economies, including Vietnam, Indonesia and Papua New Guinea, are emerging as key suppliers for primary resources and new, cost-effective manufacturing zones.

Understanding the landscape

But this huge, economically, culturally and geographically diverse region also faces substantial risks: there are political, environmental, demographic pressures - plus the threat of war. Developing an understanding of how all these factors interrelate - both now and in the future - is crucial for success.

“China and India will continue to be important alone because of their size, and the growth of their middle class,” Maplecroft principal risk analyst Julia Coym says. “That said, some Southeast Asian economies are competing with low production costs. Vietnam in particular is frequently mentioned as an alternative to China for manufacturing low-tech goods.”

War on the Indian sub-continent?

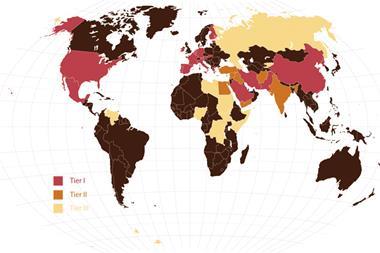

There is an ‘extreme risk’ of conflict in economic giant India, according to analysis of three years’ data by global risks analysis firm Maplecroft, with particularly strong threat posed by Islamist terrorism.

“A particular source of concern is Lashkar-e-Taiba, a pan-Islamist terrorist group that desires the creation of a ‘caliphate’ across the Indian subcontinent and the withdrawal of India from Kashmir,” says Maplecroft Political Risk Analyst Jordan Perry. “Lashkar-e-Taiba continues to launch attacks in Kashmir and India and is one of several groups suspected of the 13 July 2011 Mumbai bombings that killed at least 26 people.”

There are also still substantial tensions between India and Pakistan, which in turn faces significant internal Islamist threats. “India is also enduring a 45-year-long Maoist insurgency from ‘Naxalite’ militants in the east of the country whose aim is to overthrow the current political system,” says Perry. “The danger of conflict means that the region poses significant risks for investors - but also opportunities, if those risks can be managed intelligently.

Overall, out of 197 countries surveyed India is ranked 11, while fellow BRIC nations Russia (13) and China (29) are both rated ‘high risk’. Brazil comes in 60th, rated ‘medium risk’.

Changing demographics, principally a growing, more affluent population, mean new opportunities across the region. “While China is still the number one key market for many multinational companies, followed by India, Indonesia has in recent months been getting much more prominent,” says DLA Piper Asia head of regulatory compliance and investigation Yuet Ming Tham.

“Private wealth management [is a growth area] as more Asians become affluent. [There are also opportunities for] companies that are in the consumables business, pharmaceuticals or medical devices, simply because of the population numbers here. Also, many governments in Europe are cutting drug prices due to problems managing their budgets, which puts pricing pressures on companies that rely mainly on governments in Europe for business. But look out for constantly changing laws and regulations. It is important to be nimble enough to cope with these changes quickly and to change strategies if necessary.”

Particular industries should also be aware that both the risks and rewards the region presents are geographically specific.

It’s crucial to get advice from people who know the lay of the land. And know that countries in Asia differ vastly from one another.

Yuet Ming Tham, DLA Piper

“Get advice from experts who are out here in Asia,” Yuet Ming says. “Because it’s crucial to get advice from people who know the lay of the land. Secondly, know that countries in Asia differ vastly from one another. Thirdly, do not expect to always understand all the laws and regulations, but certainly know enough to weigh the risks against any potential upside in the business.”

“The question of key markets is quite sector dependent,” Coym says. “For example, Indonesia and Papua New Guinea are key locations for extractive companies. There’s a lot of interest and growth potential in Papua New Guinea at the moment, which despite its unstable political environment has a major LNG project coming online in the next few years.”

A different approach

It’s a complicated picture, and in response, successful organisations are rethinking their attitude to risk, taking a more sophisticated, relativistic approach. “Companies are broadening their definition to move beyond financial and operational risks,” Coym says.

“They are more aware of reputational risks and of how issues of governance, human and labour rights and even climate change directly affect their earnings and image as a company.

Many organisations are concerned with intellectual property rights, but are not paying enough attention to the legal and regulatory risks of doing business in Asia.

Yuet Ming Tham, DLA Piper

“Most companies present in Asia have some form of operational risk management in place to deal with direct threats. But most Asian nations, including large markets like China, India and Indonesia, face longer-term structural risks, which will undermine growth. These risks can include lacking economic diversification or resource security, poor labour practices or insufficient infrastructure development. Businesses need to be aware that failure by governments to address these risks within their countries will in turn impact their operations.”

“Many organisations are concerned with intellectual property rights, but are not paying enough attention to the legal and regulatory risks of doing business in Asia,” Yuet Ming says. “Even if they do so at the start of the expansion into Asia, some companies find themselves expanding so quickly they get caught out.”

The picture remains challenging and frequently further complicated by the fact many Western firms are still learning about doing business in Asia - but this is already changing. “The links between different categories of risk will become easier to see,” Coym says. “This could be through protests over poor governance and management of environmental risks, as has been the case in China recently, leading to the closure of factories. Companies will need to think more strategically and more broadly about risk if they are to manage it successfully.”

No comments yet