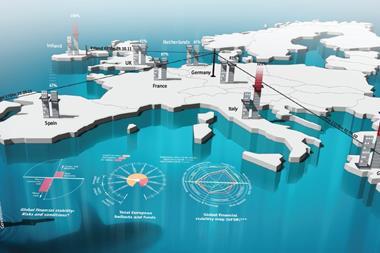

With a Greek default looking increasingly like a near certainty there are still a heap of unanswered questions surrounding Europe’s €1 trillion bailout fund

There remain a great deal of “known unknowns” when it comes to the eurozone crisis, according to respected risk analysts at Exclusive Analysis. Principal among these is the question over where exactly the extra hundreds of billions of Euros, pledged for the European bailout fund, are actually going to come from?

“We remain very doubtful that the relative optimism that has followed the EU summit will last,” said Exclusive Analysis in a special incident assessment over the weekend (October 29/30).

On October 26 European heads of state gathered in Brussels and thrashed out a last minute deal to try and fix the worsening sovereign debt crisis.

One of the headlines was a loosely agreed deal to boost the size of the European Finance Stability Facility (EFSF)—basically Europe’s bailout fund for troubled sovereigns—from €440bn to €1 trillion.

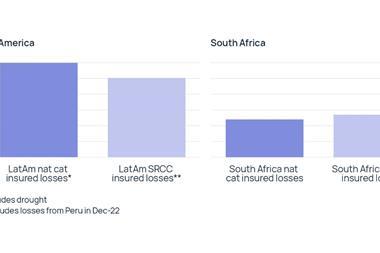

The value of the PIIGS’ debt held by the 20 most exposed banks adds up to a scary €529bn.

The problem, however, is it’s not all that clear where the extra €660bn is going to come from.

“Germany is solidly behind its commitment of €211bn,” says Exclusive Analysis. But that is at, or very near, the limit of what the Germans will offer.

To put that in context the value of the PIIGS’ (Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece and Spain) debt held by the 20 most exposed banks adds up to a scary €529bn.

China has been mooted as a possible source for the extra funds. But, according to Exclusive Analysis, China does not trust a euro system where a relatively powerless European Central Bank apparently has no control over monetary and fiscal policies.

The Chinese are also reportedly unconvinced by a monetary union that failed miserably to scrutinise Greece’s economic data when it joined.

“They are also unlikely to have found the fist fights in the Italian parliament reassuring,” claimed the analysts.

If China does contribute to the EFSF it’s likely to be for a high political price, such as purchasing strategic European banks or physical assets. Germany may not be willing to cooperate on those terms. With all this in mind a “Greek default is less a risk than a near-certainty.”

Greek default is less a risk than a near-certainty

For Exclusive Analysis the question is not about whether or not Greece defaults but rather over the way that Europe’s heavily indebted economies “recalibrate” their debts.

Could they do this in an orderly fashion (in other words the default is managed over weeks or months by politicians) or in a disorderly way (meaning the default is managed by central bankers over a weekend in a slapdash fashion, rather like the Lehman Brothers default in October 2008)?

“Clearly, we are still on the orderly transition pathway,” claims Exclusive Analysis. But a disorderly “credit event” remains a “credible scenario” over the next few months.

“Whatever happens Europe is going to experience a major redistribution of wealth.” Money will have to be printed and bad banks will need to be swallowed by good banks.

All of this adds up to a not all together pretty picture. How long it will take to reset the system and get back to normal is anyone’s guess.

Exclusive Analysis: Key Judgements

1. European leaders’ agreement to increase the size of the European bailout fund is unlikely to have an impact given the absence of clarity on where the final figure of 1trn euros funding will come from.

2. The Bundestag has sent a clear message that it will commit no more than the €211bn that it already has. China is likely to only commit token sums and then only for significant political and business concessions or perhaps physical assets.

3. The vague concepts of ‘leverage’ and ‘insurance’ that have filled the gap between what is available and what is needed are unlikely to appease anxious creditors and financial markets for long.

4. The relief of the markets seems to be that a Lehman-style credit event did not follow the Eurozone leaders meeting of 26 October, but the threat of one clearly remains. With €61bn euros of debt repayments due in February 2012 alone, Italy will likely have to reschedule.

5. The forecasting scenario choice is between a managed default and a disorderly recalibration of currencies, liabilities and obligations such as happened after Lehman declared bankruptcy on 14 September 2008.

No comments yet