Wars and financial crises are the two big threats most capable of wiping out economic growth, according to Martin Wolf, chief economics commentator, Financial Times

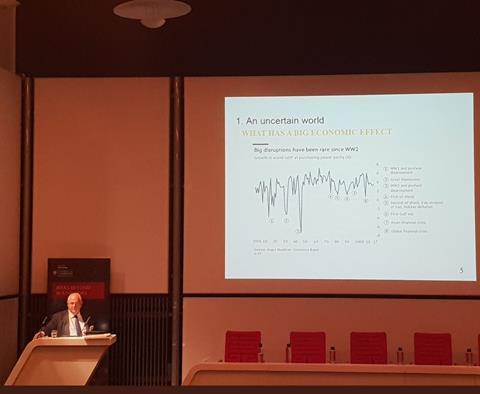

Big disruptions to the global economy have been rare in the decades since the Second World War, but two risks tend to cause the biggest economic costs – wars and conflicts, and financial crises.

That was the view of Martin Wolf, chief economics commentator, Financial Times, delivering a speech describing the cyclical behaviours that drive financial crises and make them a recurring feature of the global economy.

Wolf warned that people “get bored with peace”, citing economist Hyman Minsky that “stability destabilises” and leads to the next cyclical financial crisis.

He gave a talk as part of a Risk Summit 2018 event held in London by the University of Cambridge’s Judge Business School Centre for Risk Studies.

“We have met the enemy and he is us. We’re an extremely inventive and lethal species,” he said. “I would advise you to assume that there are going to be more of them [crises].”

Financial crises lead to greater political risk and potentially to war and conflict, Wolf warned, suggesting Europe is still, through the eurozone debt crisis and central bank policies, living in the shadow of the 2008 global financial crisis.

“This is the only sector that can demolish the world economy and it’s done it on quite a large scale several times over the past 100 years,” Wolf said. “There is nothing else in economics that generates shocks like that, other than world wars.”

He defined conflict and crises as “uncertainties” rather than risks to be managed because they cannot be reliably calculated with computable probability distributions.

Minsky moment

Wolf stressed that psychology is at least as important as economics to grasping the nature of financial crises.

Risk-takers and corporate decision-makers exhibit displacement theory, he suggested, going from thinking of a certain behaviour as risky, particularly leveraging debts in the case of finance, to considering it safe, due to the introduction of a new factor – such as new markets to play in or emerging technologies.

This cycle goes through optimism, euphoria, profit-taking and a “Minsky moment” of panic, he suggested, when crisis sets in.

Lending and borrowing behaviour shows the same cyclical patterns, Wolf explained, going through stages of interest-focused speculative finance, to Ponzi finance, expecting asset values to continually rise – coinciding with an explosion in the volume the financial sector was lending to itself in the pre-crisis years – ending in collapse.

Conclusions

The speech was subtitled “how to prevent the economy blowing up finance and finance from blowing up the economy”.

Wolf had six conclusions.

The first was that most risks we face are of our own creation, symptoms of complexity and because we destabilise our environment.

Finance is a crucial element of risk-creation, but the instabilities it creates “are endogenous: the financial sector creates its own risks”.

The more stable the environment, the more risk we take on, leading to bigger crises and recovery periods.

“We have NOT sorted out the aftermath of the 2007-2012 crises yet.”

Governments and society has been conservative since that crisis, hoping to intervene, regulate and restructure the existing system into manageability, he said.

The “Perils of Pauline” presentation title referred to an early 20th century melodrama, and the role of government interventions, regularly stepping in to save the financial services “damsel in distress” after successive crises.

“I doubt this will work,” Wolf added.

No comments yet