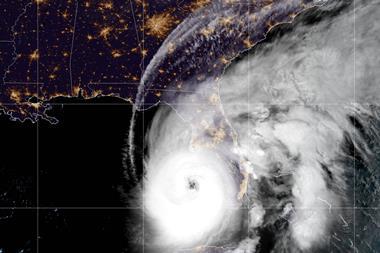

Swiss Re’s sigma report highlights the key lessons that the risk management and insurance industry must learn from hurricane Ian.

Hurricane Ian was the year’s biggest loss event, with an estimated insured loss of $50‒65 billion. This means it ranks as the second-costliest insurance natural catastrophe loss ever on Swiss Re’s sigma records.

The category four hurricane made landfall in western Florida in September, bringing strong winds, torrential rain and storm surge.

It pushed global insured losses from tropical cyclones above prior period averages, making 2022 the third most expensive hurricane season on record after 2005 (Katrina, Wilma and Rita) and 2017 (Harvey, Irma and Maria).

Lesson one: Location, location, location

Though rare, when a major hurricane strikes, the losses can be severe. As in the case of Hurricane Ian, just one peak tropical cyclone event can wreak significant damage.

Last year was “average” in terms of hurricane activity in the North Atlantic. Even so, the 2022 hurricane season is third costliest on Sigma records.

Why? Because Hurricane Ian resulted in estimated insured losses of $50‒65billion.

When Ian arrived in western Florida, it hit an area that has seen rapid population growth, expansion of built areas and accumulation of physical assets.

Since 1970, the population has increased by 620%, exceeding both the population increase in the state of Florida (+217%) and the entire US (+65%).

Swiss Re said: “Hurricane Ian demonstrates that location of landfall rather than number of storms, is the main driver of heavy loss burdens.”

Lesson two: Ongoing annual losses of more than $100billion

Swiss Re has predicted that irrespective of below-average loss years, annual insured losses will average more than $100 billion from hereon.

This expectation is supported by other parties: for example, Verisk recently modeled the global insured average annual loss as $123 billion.

Of course, in any one year losses can be higher or lower depending on whether natural catastrophe events strike urban and more populated areas.

For example, if Hurricane Ian had hit the Tampa Bay area as many predicted, the resulting losses would have been much higher. The storm demonstrated the loss potential of an individual major hurricane hitting a densely populated coastline, and the risks involved in people settling in regions more exposed to extreme weather events.

Swiss Re said: “There is no reason to anticipate that this, nor peak-loss disasters like Hurricane Katrina in 2005, will not happen again in the future.

“The takeaway is to not underestimate loss potential on account of a year or period of below trend growth.”

Lesson three: Economic factors are the main driver of elevated insured losses

There were a number of high-loss events in 2022, including Hurricane Ian, however, these losses can be explained by known risk drivers.

The industry has also experienced poor underwriting results following the step-up in natural catastrophe loss severity since 2017, new risk drivers and fallouts from the pandemic and war in Ukraine, including inflation raising the value of insured property assets.

Uncertainties around modelling discipline and the adequacy of premium levels to deal with increasing loss costs and emerging secondary perils have led to reduced risk appetite on the part of providers of capital.

So too have the recent interest rate hikes, which have increased the cost of capital. When higher exposures encounter shrinking risk appetite, rising prices, higher retentions and tighter terms and conditions result.

But even with the market reset in January, some reinsurers and investors in the sector will likely wait for signs of improved industry profits before materially replenishing capacity again.

Swiss Re said: “Historically, large catastrophe events have sparked a significant influx of fresh capital. But this did not happen after Hurricane Ian.

“ILS structures have become more exposed to loss creep and coverage disputes, and investors are hesitant to commit fresh capital to natural catastrophe risks ahead of what could be another heavy-loss year, with economic inflation adding to valuation and pricing uncertainty.

“Rising natural catastrophe losses and shortfalls in industry estimates of those losses point to the need for better understanding of all the risk drivers at play. The re/insurance industry has long monitored primary perils but this has not always been the case for secondary perils, the associated losses of which have been rising for many years.

“There is a need for greater discipline in the monitoring of the loss-driving secondary peril exposures and industry sharing of related findings. Lack of granular exposure data can also hinder understanding of all present-day risks.

“For instance, the increase in built-up land area and changes to the vulnerability of homes to hazards (eg, more solar panels on roof tops) are difficult to keep track of.

“The fast rate of change of such variables necessitates shorter update cycles of data sets and models, to mitigate risk accumulation and underestimation of loss trends.”

Lesson four: Learning from the past can improve outcomes

There was extensive wind damage to buildings in the path of Hurricane Ian. However, losses would have been much worse were it not for revisions to and enforcement of stricter building standards following hurricanes Charley in 2004 and Irma in 2017.

In the past two decades, many buildings have been constructed according to the new building standards, and many roofs have been replaced and storm-proofed.

The immediate surroundings of Hurricane Ian’s landfall location also suffered extensive storm surge. Water levels exceeded 4-5 metres in the Fort Myers Beach area and affected homes up to 0.5 km inland. While many buildings are wind-proofed, there is lack of “proofing” for high waters.

Swiss Re said: “The takeaway is that more investments in flood protection and existing infrastructure are needed. In addition, further improvements in flood protection will support adaption to climate change effects, one of which is the heightened risk of coastal floodin

No comments yet