While energy insecurity has sped up the transition in Europe, it has pushed some Asian countries to rely more on fossil fuels

Asia has become the fulcrum of a global tussle centred on the energy transition, which is reshaping climate politics and economic interdependencies, according to Verisk Maplecroft.

The analysis identifies three key trends driving these new geopolitical rifts, including an expanding global division on climate politics; the shifting of fossil fuel supply chains towards Asia; and the region’s rising dominance of green energy markets.

“The global division on emissions has brought many developing countries together in terms of their climate politics,” says Kaho Yu, head of Energy Markets at Verisk Maplecroft.

Most notably, despite their ongoing border tensions, China and India jointly led a last-minute intervention to weaken the language on fossil fuels in the Glasgow Climate Pact at COP26. Their negotiating position calling for “climate justice” benefits from the support of many cash-strapped economies.

“We expect these developing countries to stand together as a bloc negotiator and press rich countries for more support in climate finance, mitigation and adaptation,” adds Yu.

The implications of these trends are far-reaching. They not only provide traditional oil and gas producers breathing room among ever louder calls for divestment from fossil fuels, but they also allow China to continue to utilise the strength of its market for geopolitical advantage amid a global energy crisis.

The North-South divide

The Russia-Ukraine crisis has deepened the global division on climate action. While energy insecurity has sped up the energy transition in Europe, it has also pushed some Asian countries to rely more on fossil fuels to ensure basic supplies.

Although opportunities in Asia for renewables remain robust, major emitters have doubled down on coal to ensure basic energy supplies. For example, the People’s Bank of China has increased special loans for clean and efficient use of coal to $45 billion, almost four times more than the financial support for renewables.

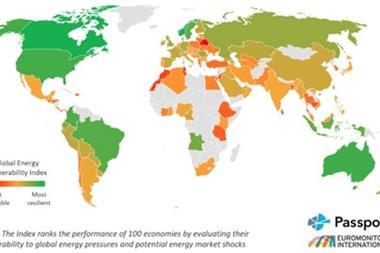

Lower income countries, those with weaker scores on Verisk Maplecroft’s Poverty Index, are less likely to adopt a stringent carbon policy. Despite carbon neutrality pledges, these countries have prioritised domestic development agendas, such as poverty eradication, economic growth and energy security.

Their economies are more sensitive to the social impact of a robust carbon policy, such as unemployment caused by less investment in fossil fuels. Therefore, developing countries, especially China and India, will likely take a much slower transition path than developed countries, such as the US and EU, warn the researchers.

No comments yet