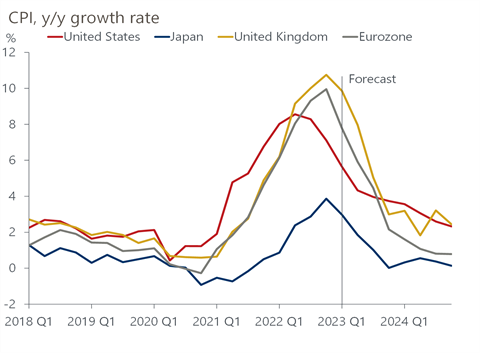

Global inflation will return to pre-crisis levels faster than it took to reach its peak, but any number of shocks could derail this outcome

Across the advanced economies, inflation is now expected to fall back decisively in 2023, according to insights from Oxford Economics. These expectations rest largely on falling energy prices which were the main culprits of the inflation take-off to begin with.

Looking at the main inflationary culprits – energy and food prices – there is evidence to suggest that pandemic-era pass-throughs were higher than has historically been the case.

With global food and energy prices returning to historical levels, it seems likely that bigger margins of the past two years will result in a faster pullback in inflation now.

Inflation has decidedly been an advanced economy phenomenon this time around, a first after decades of it being a characteristically emerging markets problem, the economic thinktank points out.

Post-pandemic, emerging market inflation rose relatively less. Early, decisive policy tightening in emerging markets certainly helped as did the concerted effort with the advanced economy central banks once they joined the ranks of rate hikers.

The difference between the two speaks to the role played by policy-driven demand push in advanced economy inflation.

Energy and food prices in retreat

If companies, aided by pent-up demand, were able to pass along increases in energy and food prices onto consumer prices, making the pass-through both higher and perhaps faster, then you should expect a retreat in both oil and global food prices to produce an equally swift turnaround in overall inflation.

The logic behind this reasoning is economic rather than statistical – if margins are already higher than usual, then it would be reasonable to expect margins not to increase further and perhaps even shrink. Coupled with lower commodity prices, this would produce a faster pullback in total inflation.

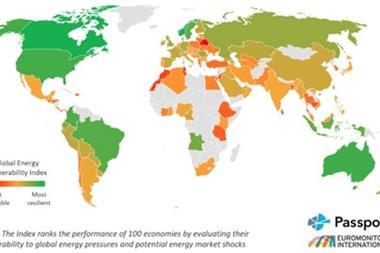

In terms of global energy and food prices, both now are in retreat. While gas prices in Europe are still elevated, their levels are now well below their peaks and the heights they were expected to be at now.

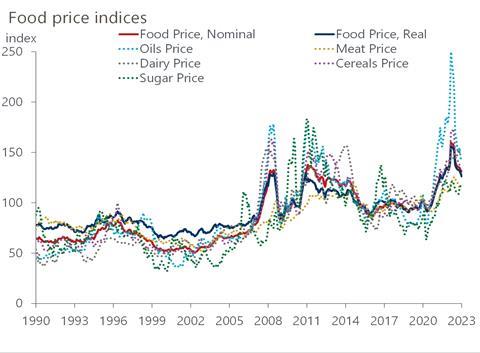

Similarly, food prices have changed course – oil and cereal prices (both heavily affected by Ukraine war) are still above their historical levels, but the global food price index is edging decidedly lower and towards average historical levels.

Looking at 12-month rolling correlations between the US CPI inflation and WTI oil price on one hand and the FAO food price index on the other hand, suggests that the past two years have indeed been characteristic of a higher than usual correlation between the two – higher pass through from commodity prices to consumer prices.

When will inflation settle?

From a purely mechanical perspective of inflation dynamics, which the thinktank tries to capture with machine-learning algorithms designed to discern patterns within goods and services prices, it seems likely inflation will decrease rapidly this year.

Its data mining techniques, however, cannot answer the question of where inflation will settle. That answer likely lies in the labour market dynamics. Wages now seem to be turning too but it is still too early to tell whether it will be enough to declare victory over inflation, concludes Oxford Economics.

”What remains to be seen is just how far inflation falls – will we go all the way down to the central banks’ target of 2% or will inflation settle at a higher level?” says Tamara Basic Vasiljev, senior economist.

”For now, data alone cannot answer that question, not with machine learning algorithms, passthrough analysis, or any other technique. The answer probably lies in how wage negotiations evolve from here and how people decide to spend the accumulated savings that remain in their bank accounts.

”The risk of wages proving sticky on their way down just as they did on their way up are non-trivial. Equally non-trivial are the chances that pent-up savings keep propping up retails sales (and inflation) in the face of a slowing economy.

“For more clarity on both questions, we will have to wait for a few more months of data on wages and savings.”

No comments yet