Key challenge for companies is to determine traceability of their often highly complex supply chains

On 23 December 2021, President Biden signed the much-anticipated Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA) into law, marking a further ramping up of efforts by the US to counter forced labour in China’s Xinjiang province.

The UFLPA’s requirement to “ensure that goods mined, produced, or manufactured wholly or in part with forced labour… are not imported into the United States” requires a level of traceability that most, if not all companies, are likely to find incredibly challenging, notes Sofia Nazalya, Asia analyst at Verisk Maplecroft.

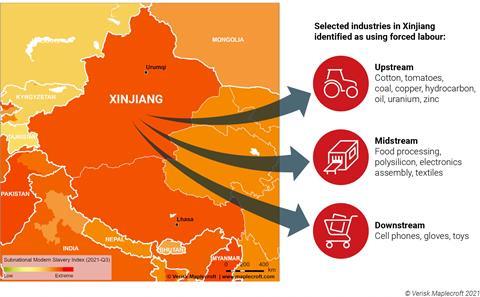

“While previous actions targeted specic products, such as the US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) ban on imports of cotton and tomato products in January 2021, the presumption of forced labour region-wide effectively prohibits the importation of all goods arising out of Xinjiang,” she explains. ”This will therefore have signicant disruptive impact across multiple sectors.”

Companies seeking to continue the import of Xinjiang goods must provide “clear and convincing evidence” that the goods were not manufactured with forced labour, shifting the burden of proof away from customs officials.

“The addition of polysilicon alongside cotton and tomato products identied as “a list of high-priority sectors for enforcement” is unsurprising given Xinjiang’s status as a major producer,” continues Nazalya.

“However, as we have argued in our previous analysis, while enforcement of the Act will be prioritised in these sectors, other industries must also brace for impact.”

Apparel firms must go beyond tier one

The extension of the forced labour presumption region-wide is likely to make the importation of Xinjiang goods too fraught with legal and operational risks for it to be practical for many US companies.

”Most apparel companies are likely to have already implemented contingency plans or are in the process of doing so,” says Nazalya. “While it is clear that the UFLPA will cause sizable disruptions requiring companies to relocate, or at the very least, strengthen their due diligence processes of their Xinjiang-linked operations, the question remains of its efficacy to prevent the occurrence of Uyghur forced labour in supply chains.”

”Reports suggest that more than half of China’s exports of cotton semi-finished products are exported to Asian garment manufacturing hubs, where international intermediary factories produce finished garments.”

”For apparel and textile companies to adequately meet their legal obligations under the UFLPA, they will have to ascertain that none of the cotton that goes into the garment production of their extensive, and very often highly complex, factory supply chain is sourced from Xinjiang.”

“The same is true for the solar industry – and given that Xinjiang accounts for an estimated 35% to 40% of the global silicon trade, this will be no easy feat.”

The complex nature of global supply chains will make it “immensely difficult” for affected companies to confidently guarantee that they are in no way, shape or form sourcing from the region, concludes Nazalya.

”For companies, their compliance pathway must extend beyond ensuring that their Tier 1 suppliers are not located in Xinjiang. The ability to fully map out supply chains to include the suppliers of intermediaries, is key to having a more accurate picture of a company’s exposure to forced labour in Xinjiang.”

”Without this, Xinjiang products – namely cotton, agricultural products and polysilicon – will continue to nd its way into international supply chains, meaning companies may continue to inadvertently profit from Uyghur forced labour.”

No comments yet