By Lee Coppack

In less than a year, the International Society of Catastrophe Managers (ISCM) has attracted nearly 400 members, conducted two successful conferences in co-operation with the Reinsurance Association of America and the International Underwriting Association in London, and held additional regional meetings in New York, Paris and Zurich. More events are planned.

There has never been more science applied to the underwriting of catastrophes than now. Yet, it seems that catastrophe modellers feel that they have been made part of the engine room of the insurance and reinsurance industry, and that what senior management wants from models is a reading from a gauge and not advice on which direction to steer.

The people who make cat models and work with them are scientists and people from other technical and quantitative disciplines, like engineering. They are interested in the functionality of the models and differences between them. They get frustrated when they cannot take the machine apart and see how it all works.

Senior managers, on the other hand, are also working with models, but different ones that span the enterprise as a whole, under the surveillance of regulators and rating agencies. Catastrophes are one variable in that model, along with interest rate movements, liability claims, competition, regulation and tax, among many other factors which determine the profitability of the business.

Senior managers do sometimes need fairly straightforward answers to questions like – how many, how big, how bad and how reliable are these answers. Competitive pressures prompt another question – how far can we go on pricing without getting into trouble?

There is also the question of time scale. Scientists also tend to deal with the careful collection of evidence and with slowly developing trends. Insurance and reinsurance companies are expected to respond almost instantaneously to investors and analysts who are one step further removed from the catastrophe model issues. The stock market wants fast estimates, so analysts can adjust forecasts and investors act. The finer points of modelling may be a casualty in the immediate aftermath of a catastrophe.

Even if the modellers believe, probably with justification that these questions ask for over-simplifications in response, the pressures will not change. If anything, they will grow as trading in capital market catastrophe securities becomes more important.

There is little gain in objecting that tigers are striped. Cat modellers need to communicate in ways that make business sense. The best of them already do. From an understanding of thepressures and demands that industry faces, they may also find new business opportunities.

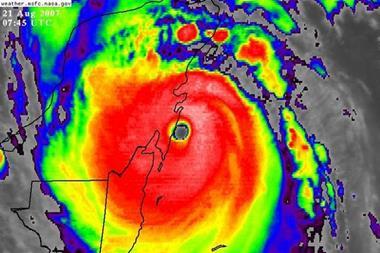

Model users need also to listen to a variety of views about risk and make their own observations. If there is an obvious gap between what their understanding and experience indicate and what the models say, then they should question the modellers. As Hurricane Katrina demonstrated, the building vulnerability functions may not be as strong as other elements in even the most highly developed models. Claims experience may provide valuable additional evidence, for example, of the quality of local construction.

The modelling of all sorts of scenarios, from congestion charging for traffic to the behaviour of financial markets, has become very sophisticated as techniques and computer power have developed. Models are, nevertheless, still theoretical and can come apart in the face of natural events and human behaviour.

Financial institutions just bristling with mathematical brains can come unstuck because their models usually work on the basis of past behaviour and cannot anticipate changing circumstances unless the modellers have imagined them.

In August 2007, the mighty Goldman Sachs admitted its models had failed to foresee market movements triggered by the crisis over US housing loans. It described them as 1 in 100,000 year events — but they and other unpredicted events occur.

Natural catastrophes and their effects on the built environment are even more complex and subject to even more uncertainty than financial markets. Models of them are, inevitably, much simplified versions of the events they are trying to represent. Aspects of risk that are not well modelled or modelled at all, such as forestry losses in Scandinavia, may still be covered in an insurance or reinsurance policy.

Even if the gauges on the engine are giving a satisfactory reading, it is still worth investigating strange noises. Like ill-understood and unpriced risks, they may turn out to be nothing or could result in a large machinery damage loss.