International litigation is on the rise, with an increasing number of claimants turning to the UK courts to resolve their disputes

A bulletin on fines for health and safety breaches hardly sounds like bedtime reading but its perusal should certainly be obligatory in boardrooms. Issued by Field Fisher Waterhouse, this seemingly innocuous publication is a symbol of the explosion in litigation faced by UK companies as employees, consumers and various authorities mount often expensive and reputation damaging cases for alleged failures to observe the law.

Three cases that illustrate the ever-present risks of prosecution for health and safety breaches alone. All of these judgments were handed down in the past few months.

After developer St George South London commissioned signage company AE Tyler to advertise a property, the sign unfortunately collapsed on an individual and caused permanent brain damage. The consequent fine for both parties amounted to £360,000 (€429,000), not counting the £250,000 costs.

When an employee died after an accident at Nolan Recycling Waste plant, the fine came to £250,000 with £53,000 costs on top.

And when a worker at Aesica Pharmaceuticals suffered severe skin burns and damage to one eye as a result of being sprayed by a toxic chemical, the company was ordered to pay £100,000 in fines and nearly £8,000 in costs.

Litigation capital

The bulletin makes for sober reading, not just for the misfortunes of varying severity suffered by the individuals, but for the mounting risks that all employers face from almost any kind of injury incurred on their premises.

As Field Fisher Waterhouse corporate risk management group dispute resolution lawyer Rhys Griffith says: “The fines and costs which may flow from safety-related incidents can be significant, not to mention the reputational stigma the company will suffer.”

And litigation is very much on the rise in the UK. Indeed London could be turning into the litigation capital of Europe. According to The Lawyer, the number of international litigants turning to the commercial court to resolve disputes has grown by an average of 10% a year in the past three years. Over a five-year period the volume of European-based litigants taking their cases to the capital soared by 165%.

Unsurprisingly, across the Atlantic the risks of prosecution are rising all the time. All Europe-based companies with US operations face an increasingly complex litigation scene. As US litigation specialists Crowell & Moring’s chairman Kent Gardiner says in the firm’s latest litigation forecast: “Everything from protecting innovation to protecting contracts to growing through acquisitions and avoiding compliance penalties may be at stake [in these cases].”

As an indication of the growing aggression of state agencies, a phenomenon that is also reflected in the UK and Europe, Gardiner estimates that two-thirds of the firm’s lawyers litigate before federal and state trial appellate courts and before government agencies.

In the UK as elsewhere the law makes prosecution a relatively easy matter, and especially so for consumers. How many of Britain’s hotel owners know, for example, that they are strictly liable for the loss of property brought by their guests unless they can prove that the item went missing because of the guest’s own negligence?

As commercial barristers Quadrant Chambers’ Thomas Macey-Dare says, this strict liability dates from the Middle Ages when inn-keepers were often in league with highwaymen to rob guests while they slept.

These days the law is enshrined in the Hotel Proprietors Act of 1956. Although the proprietor’s exposure, being limited to £750 per item and £1,500 in total, would hardly put the business at risk, it does demonstrate how vulnerable businesses can be to events that may be only technically within their control.

As businesses expand beyond their home base, directors may be increasingly open to another country’s system of litigation. In Australia, law firms have identified a trend towards piercing the ‘corporate veil’ that is putting directors’ personal assets and even their freedom at risk.

“For many years the corporate veil has been under attack to the point where, according to some, it’s been reduced to little more than a tattered rag,” says Stacks/The Law Firm business law specialist Tony Mitchell.

The Australian corporate watchdog ASIC has been particularly aggressive in recent cases. As Mitchell says, directors can be held personally liable for a string of misdemeanours including unpaid superannuation, allowing the company to continue to trade when there are grounds to suspect it may become insolvent, failure to exercise a reasonable degree of skill, failure to disclose material personal interests and other alleged breaches of their obligations.

“The continuing deterioration of the corporate veil means it is more important than ever for company directors to develop and have in place appropriate strategies to protect their personal wealth and their families’ wealth,” Mitchell warns.

As in other jurisdictions, the risk of prosecution by aggrieved consumers is also growing. Take door-knocking, a sales technique that does not normally attract the ire of consumer watchdogs. But when energy group AGL sent out salespeople who failed to reveal, as required, that they were in fact salespeople and then compounded their mistake by misleading homeowners on the company’s pricing, the result was a whopping total penalty of A$1.75m (€1.22m).

Proactive approach

And from the serious to the ridiculous, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission lately took a company called Turi Foods to court on the grounds that its chickens were not “free to roam around in large barns” as advertised. The ACCC argued that in fact the chickens were “subjected to such stocking densities that they do not, as a practical matter, have a substantial space available to roam around freely”. As is usually the case, the ACCC won and penalties are yet to be decided.

Increasingly, litigation over allegedly defective products is going international, as an un-named German bike manufacturer discovered when a teenager was badly injured after the front fork of a Taiwan-assembled, A$1,200 bike collapsed in Australia. As lawyer Ben Stack of the firm of the same name aptly put it, “what followed was an international conga line of blame”.

It surely was. The boy’s lawyers sued the importer, who sued the manufacturer, who sued the Taiwanese sub-contractor who made the part, and who then sued another Taiwanese manufacturer that fitted the same part to the bike. On the fourth day of the trial the defendants settled for an eight-figure sum.

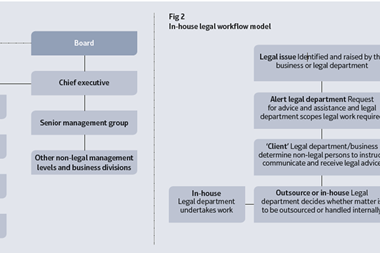

So what can a company do in the face of such a diverse array of potential prosecutions? Get a lawyer, obviously. And even better, suggests Crowell & Moring’s Gardiner, make it an in-house lawyer.

“For corporate legal departments today, success demands a more proactive approach than hiring outside counsel [in order to manage] costs. In-house lawyers need to know more than ever [if they plan] to succeed, both about their clients and the legal landscape,” says Gardiner.

The good news is that, in England and Wales at least, a professional defence may not be as costly as many companies think. Six months ago it became legal for firms to charge their clients contingency fees, which essentially permit them to offer a range of funding arrangements to suit the requirements. For years, commercial clients have asked for flexibility and certainty in costs and some risk-sharing by their lawyers.

It is fair to say most UK firms have resisted taking on cases against contingency fees (although it has long been normal practice in the US), but that is now changing. Field Fisher Waterhouse, for example, has introduced a package called FeeSolve that, it says, does the job. Given the litigation that may be looming over the horizon, this could prove a popular innovation.

No comments yet