Maersk’s costs from NotPetya and the prospect of more cyber-attacks like it raise concerns about cyber risk and resilience for shipping and maritime logistics firms. David Benyon reports

Shipping industry firms and port operators are worried about linkage between the proliferation of cyber-attacks and their supply chain risks. The sector is moving towards greater connectivity between its various systems, particularly for ship to shore communications and systems on the bridge of vessels, such as GPS, electronic charts and E-navigation.

Big interdependencies between systems also mean shipping, ports and logistics firms face business continuity risks in the face of online threats. Recent attacks have shown the industry faces severe cyber resilience risk, with heavy business interruption losses for firms such as Maersk already hit. With that in mind, there is a growing realisation that improving cyber resilience is a serious challenge for the maritime sector to address.

“The problem is that nobody knows, other than the computer systems, where your goods are,” says Pascal Matthey, head of global lines for marine risk engineering at XL Catlin. “You might never find your container again. Refrigerated containers might lose power, which would mean huge damage.”

Supply chain risks have increased with the size of vessels. The biggest ships can put in at fewer ports, and the sheer volume of cargo or containers aboard a single vessel adds to the concentration of risk and globalised economic fallout if something happens to a ship.

“If an oil tanker misses a delivery, a company can be done for. It’s their reputation, their contracts, and them being made liable for not delivering,” says Sjaak Schouteren, a cyber risk insurance broker at JLT, based in Rotterdam. “But the main risk is not liability, it’s business interruption, and getting back on track.”

Schouteren cites a maritime breakdown that caused a loss event for a retailer. “A case happened a couple of years ago when a large ship broke down and the whole stock for an international retailer for the season was on that vessel,” he says. “That’s not good risk management. By the time you get those swimsuits back, summer is over.”

Cyber risk at sea was the subject of a recent paper, “Risk Focus: The maritime supply chain cyber threat”, published in March 2018 jointly by the UK P&I Club, a protection and indemnity (P&I) liability mutual insurer for shipping firms, TT Club, a mutual for transport and logistics sector firms, (both firms are managed by Thomas Miller, an insurance services provider), and NYA, a security consultancy and crisis response firm working with insurance market and direct clients.

The paper stressed that the increased use of automated and digital systems is exposing the maritime sector to greater risk from cyber-crime. “As the industry embraces technology, the exposure and threat continue to grow and therefore with every process in the shipping industry that is automated and digitised, risk assessments need to be carried out to mitigate against potential new threats and vulnerabilities posed by these evolving cyber threats.”

Research in 2017 carried out by SeaIntel, a maritime sector analysis firm, revealed that 44% of the top 50 shipping carriers had weak or inadequate cyber security policies and processes, “including weak passwords, delayed installation of security patches and the use of unencrypted web browsers”.

Another piece of research, conducted in 2016 by BIMCO, the largest shipping association, and Fairplay, a maritime data provider, revealed that 21% of respondents from the maritime sector admitted to previously falling victim to cyber-attacks.

“However, the actual number of victims is likely to be higher for two reasons,” said the study. “Firstly, not all victims are likely to admit to the security breach particularly to avoid potential reputational damage. Secondly, it is highly likely that more victims are being targeted but effective security measures already in place are either mitigating the impact of the attack or preventing successful breaches.”

NotPetya hits Maersk

Weaknesses were revealed at shipping giant Maersk last year. The NotPetya contagious malware attack struck a range of companies in June 2017, barely a month after WannaCry, another malware outbreak.

NotPetya (unimaginatively named to distinguish it from antecedent versions of the Petya virus), caused global economic losses of $2.5-3bn, risk modelling firm Risk Management Solutions (RMS) has estimated.

Shipping logistics firm AP Moller-Maersk was one of the organisations worst affected. From 27 June 2017 NotPetya caused congestion in as many as 80 ports worldwide by infiltrating its APM Terminals port services arm. The business was forced to temporarily switch to manual systems – pen and paper, and employees’ personal email addresses.

Maersk had to reinstall some 4,000 servers, 45,000 PCs, and 2,500 applications. That onerous business continuity task took 10 days and cost the company around at least $300m initially and perhaps $450m in total to fix.

“It shut down the shipping business across global ports…they had to return to pen and paper,” said Andrew Coburn, senior vice president at RMS and director of the advisory board for the University of Cambridge’s Centre for Risk Studies, speaking at a cyber risk event held in March in London.

Global logistics firm FedEx was high up the list of other multinationals badly hit. Deutsche Post DHL was also affected, albeit to a lesser degree. FedEx suspended its share dealings on the New York stock exchange after reporting $300m costs from its TNT Express division in lost business and clean-up costs.

“Maritime sector companies didn’t know to what extent something like this could hit them, and how intertwined their risks were in the supply chain,” says JLT’s Schouteren. “They are certainly looking at that now, and trying to protect themselves, through security arrangements and with insurance. We ask clients: ‘what are the crown jewels, and what can cause you the biggest headache if a system goes offline, is inaccessible, or is accessed by others.’

“Shipping companies are also increasingly looking at the firms they do business with and asking if they’re protected, too. Companies are so reliant on other operators in this sector. They’re looking at the whole infrastructure and asking if it’s resilient,” he adds.

Coburn described the NotPetya virus as a “destructive disk wiper” rather than ransomware. Users received messages demanding payment, but there is no sign that paying the ransom request led to any access to data being restored.

“This untargeted incident highlights the shipping and logistics industry’s vulnerability and perhaps more importantly, the need to adopt appropriate response protocols,” said the cyber risk focus report. “Given this current state and increasing automation in the maritime and logistics industry, it is inevitable companies will require a robust information security management system.”

Collateral damage

Most attacks are not targeted at maritime firms, yet they fall victim all the same. NotPetya was likely a cyberspace example of Maskirovka – Russian military deception techniques – as observed in the real-world in Crimea and Ukraine.

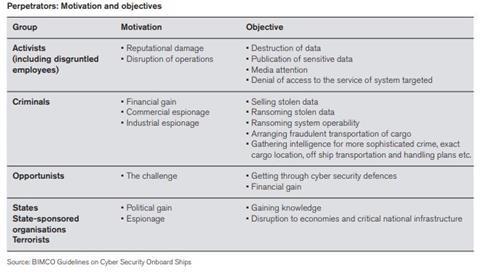

Such tactics are designed to initially confuse the victim about an attack’s nature, and therefore its likely source, to paralyse, deflect blame and delay an effective response. The motives, objectives and groups behind cyber-attacks are myriad and diverse (see table 1, above).

The US and UK governments would eventually blame the Kremlin for NotPetya, but condemnation did not come until February 2018, by which time it had emerged that 75% of NotPetya’s damage was focused on Ukrainian organisations.

Collateral damage is a risk of weapons of war, and NotPetya, spreading via financial transactions, caused disruption to more than 30 large, global companies across 65 countries. Maritime and logistics specialists Maersk and FedEx were among the firms caught in the crossfire.

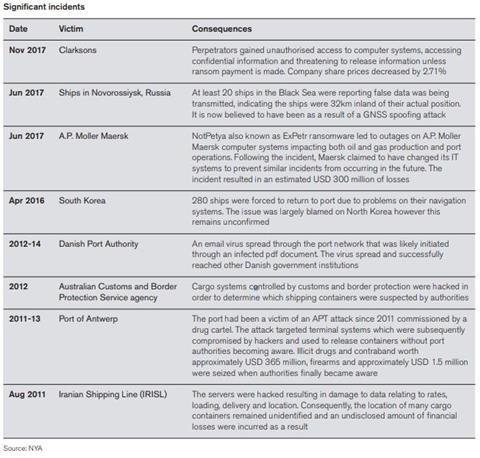

This may have been an alarm call for businesses, but it is not the first time it has rung for maritime and logistics industries (see table 2, below).

Another cyber-attack, revealed in 2013, struck two shipping companies operating in the Belgian port of Antwerp, and had reportedly gone undetected for about two years before that.

An organised crime group allegedly used hackers to infiltrate computer networks, allowing cocaine and heroin, hidden in containers shipped from South America, to be intercepted by criminals. Illicit drugs and contraband worth approximately $365m were eventually seized, as well as firearms worth $1.5m once authorities had cottoned on.

With this attack, again, the maritime sector was not the actual target, just another mule for the drug gangs, but that did not protect firms from the fallout. “The idea was not to harm the port but to get things out by hacking the system,” says Matthey at XL Catlin.

The Antwerp attack began by targeting employees with emails designed to infect their systems with malware. Such Advanced Persistent Threats (APT) attacks prey on human weakness – usually the weakest link within cyber defences.

Phishing, social engineering, and so-called man-in-the-middle scams target the maritime and logistics industry as they do other sectors. Human error is universally acknowledged as the main vulnerability for such attacks, such CEO scams.

Spyware has led to emails being monitored, helping criminals commit fraud by impersonating a senior manager or a supplier asking for payment, made instead to the criminals’ account.

The cyber risk focus report said: “These incidents have caused a significant financial impact, with one Malaysian bunker company losing $1.1m to the scam. In this case the bunker company made two separate payments, the first on 31 May 2017 and a second on 2 June 2017. The payments were issued following receipt of a genuine looking invoice that sought to channel payments to new banking account details.”

Targeting ships

Matthey cautions about the catastrophic consequences of a potential cyber-attack by terrorists, such as targeting a ship, or multiple vessels, and interfering with steering, propulsion or navigational systems to cause a collision in the congested waters of a busy port or a major trade artery such as the Panama Canal.

“What happened on 9/11, you could perhaps now do with a ship, by steering a large vessel into an oil or gas terminal, which could have disastrous consequences,” Matthey warns.

There have already been examples of jamming and spoofing of ships’ Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) and Automatic Identification Systems (AIS), which use GNSS data. In 2013, a study at the University of Texas exposed that hackers can intercept the satellite signals, like a “man-in-the-middle” attack, and feed false information to vessels. The result is that ships can appear to be somewhere they are not.

“On the dark web, servers for satellite AIS could be hacked. This potential vulnerability has not yet been exploited,” says Ghonche Alavi, an information security consultant at NYA Risk. “If you can veer a vessel off course and shut off its AIS, it’s very difficult to locate it. It could then be a prime target for hijackers. That would be a sophisticated attack for pirates to pull off, and we’ve not seen yet, say in the Gulf of Guinea piracy hotspot off West Africa. However, these things are easily purchased on the Dark Web and the technology can be easily exploited, so I can’t imagine why it could not happen.”

In April 2016, some 280 ships had to return to port due to problems with their navigational equipment, in an incident blamed on North Korea. In June 2017 at least 20 ships in the Black Sea were reporting false data was being transmitted, indicating the ships were 32km inland of their actual position. The incident is thought to have been a GNSS spoofing attack, according to NYA.

“Navigation experts claim the spoofing sent false signals and resulted in the receiver providing false information. There is speculation that this incident could have been a Russian state-sponsored attack with over 250,000 cell towers reportedly equipped with GNSS jamming devices in Russia, however at present this incident remains unconfirmed,” said the cyber risk focus report.

A state-sponsored attack might seek to misdirect a vessel so that it strays into territorial waters, creating diplomatic waves. “It’s cheap to have a jamming device installed on a cell tower. There is suspicion that Russia has put jammers on its cell towers, but this has never been verified,” says Alavi.

Malware and ransomware attacks on ships’ Electronic Chart Display and Information System (ECDIS) are feasible. ECDIS is a geographic information system used for nautical navigation. “ECDIS is updated locally, so it is feasible to have the screens on the bridge blacked out by malware and ransomware,” Alavi says.

Converging systems

Increasing convergence between IT and operational technology (OT) systems is a trend common to many industries. Collecting more data, and analysing data to drive business efficiencies or opportunities is necessary for technology trends such as the Internet of Things and for Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Driverless ships – predicted to one day ply the world’s oceans – will rely on vessels’ various IT and OT systems talking to each other and the AI seamlessly. But the necessary convergence between systems is already taking place, on vessels at sea and in ports, increasing the potential severity of damage that a cyber-attack could cause. Although so far very few vessels are driverless, almost all ships are lightly crewed, adding to the pressure on crews if linked systems start to go wrong.

“We are seeing convergence between the IT and OT systems,” says Alavi at NYA Risk. “The way OT is typically structured is to be robust and isolated from the IT systems. Now it is being converged with the IT systems, meaning that any malware that gets into the network architecture can also impact how the OT systems function.”

This is a risk for ships out at sea as well as for the critical port infrastructure ashore that handles the vast amount of cargo that keeps the global economy humming.

“On the bridge of a vessel, several key functions are carried out that link IT and OT systems together,” says Alavi. “In ports, the cargo handling equipment is monitored and organised by the IT, but relates directly to the OT responsible, for example, for moving the containers. Architecture varies, but because people may not have looked at the overall blueprint, systems are vulnerable, and lives could be at risk, if the IT systems controlling the OT are not protected adequately.”

Schouteren at JLT notes that for OT systems, the most important thing is availability, otherwise you get business interruption. Conversely, when you look at IT security, confidentiality and integrity are the priority.

“The systems are not built on the fact that they are IT-based,” he warns. They are not based on being lined up with the internet. The OT systems are based on being accessible and available all the time, but they are not secure.”

Rules of the road

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) Resolution MSC.428(98), introduced on 7 June 2017, prompts the shipping community to understand cyber vulnerabilities and how they could affect operations. The IMO resolution requires organisations to take the necessary steps to incorporate cyber threat considerations appropriately through safety management systems and address this by the first annual verification after 1 January 2021.

Industry group BIMCO recommends plans to consider “ship to shore” connections. Cyber security as part of ship safety management systems should include measures to prevent, detect and respond in the event of a cyber incident. Ship to shore communication typically includes: very-small-aperture terminal (VSat); wireless networks (Wifi); fleet broadband (FBB); fourth generation broadband cellular (4G); very high frequency radio (VHF); the Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS); and a ship’s AIS.

Last year, the US Coast Guard issued a draft Navigation and Vessel Inspection Circular (NVIC) 05-17 titled ‘Guidelines for Addressing Cyber Risks at Maritime Transportation Security Act (MTSA) Regulated Facilities’. The draft would require incorporation of personnel training, drills and exercises to test capabilities, security measures for access control, handling cargo, delivery of stores, procedures for interfacing with ships and security systems and equipment maintenance. The guideline also recommends controls in place to protect, detect, respond and recover to cyber breaches.

Meanwhile, regional directives and legislation such as the Directive on Security of Network and Information Systems (NIS directive) and EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) are indicative of the growing importance of cyber-security in the minds of lawmakers.

Schouteren spies trouble on the horizon because of potentially conflicting regulatory environments. “Vessels are moving around the world, and there are different policies in place for different geographies. It’s going to be a big thing to comply with various regimes across the world. Different ports have different regulations” he says.

Ultimately, the main cyber risk is business interruption, and it continues to derive from human error more than any other single vulnerability, although IT and OT systems converging and joining together is potentially compounding cyber risk.

“Mostly it goes wrong with the people on the ships, who have never heard of GDPR or an ISO standard,” says Schouteren.

The cyber risk focus report warns: “As the feasibility of a more damaging attack increases, all stakeholders – in particular ports and terminals, and shipowners and operators alike – must prepare for the inevitable. Appropriate plans and processes need to be established and enforced to mitigate against this growing threat.”

No comments yet