Geopolitical and economic uncertainty is fuelling the growing uptake of political risk covers. By taking a more proactive, analytic approach, corporations can elevate this coverage from a risk transfer transaction into a strategic tool. By Antony Ireland

Political risk spans a broad and amorphous bucket of perils, from financial risks such as contract abrogation or non-payment by sovereigns or private companies to government confiscation of assets, civil commotion and political violence.

During the Arab Spring, many multinational corporations’ minds were drawn to the risks associated with conflict and how this could affect their assets and businesses, but in recent years the destabilisation of the global political landscape has brought credit and economic uncertainties firmly to the fore.

From the unpredictability of US policy and worsening US relations with Russia, China, North Korea and Iran, to tensions in the China Sea, Crimea and the Middle East, today’s political landscape is tense, unstable and constantly evolving.

Then there are ongoing economic uncertainties, from foreign exchange rates, Brexit and commodities prices to interest rates and central bank policy. These are indeed politically risky times, and this is manifesting itself in a worsening credit environment for companies doing business in many markets around the globe.

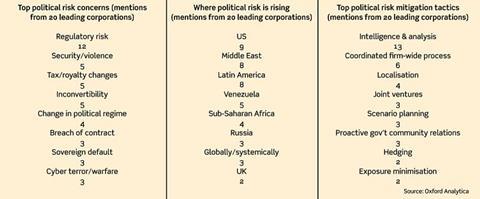

“We are definitely seeing an uptick in non-payment claims activity, particularly on sovereigns defaulting,” says Claire Simpson, global claims director, financial solutions, for Willis Towers Watson (WTW), who notes that in an environment of prevailing geopolitical uncertainty, regulatory risk is “far and away the top concern” of many international organisations.

“The heightened risk of finding yourself operating under contract in a jurisdiction where a legal change or new tax regime is introduced can make it difficult for multinationals to plan ahead.”

A survey of panelist at 20 leading corporations by WTW and Oxford Analytica late last year found that 89% of those interviewed felt political risk levels have increased over the past five years, and 63% had experienced a recent financial loss because of political risk.

According to WTW, political risk levels and volatility are expected to remain elevated in part due to a lack of clarity about global leadership, with US policy volatility, populism, protectionism and US sanctions on Russia all key concerns. “The pre-global financial crisis environment looks incredibly benign compared to today,” says Simpson.

Meanwhile, politically motivated regulatory change is having a significant impact on corporate risk exposure, with implications for tax rates, cross border trade and exchange transfer risk. As one survey panelist put it, “there is major uncertainty among the major industrial territories and how they will interact with each other”.

Rising political risk in the US could have a material impact for businesses not just trading directly with the US but also with countries whose own economies could be affected by US policy. “The US is unlikely to be the direct cause of losses on our side but could well be a contingent creator of a risk dynamic that affects us, such as tit-for-tat trade retaliation,” says Peter Jenkins, political risk divisional director for Brit Insurance.

And with the US a less predictable stabilising force on the global stage, certain governments may be emboldened to “investigate their own agendas” without fear of being kept in line, he adds.

Indeed, sources report that while claims activity still persists in the ‘usual suspect’ countries that have historically proved risky trading environments, including Venezuela, Egypt, Russia, Nigeria and a host of other nations in Latin America, Asia, Eastern Europe and Africa.

“Some territories that we used to cover routinely 20 years ago we never see anymore because they’re now a part of European Union, for example, but there are many emerging or frontier market countries that were regular names back then and are still regular names now,” says Jenkins.

One of the key issues increasing credit risk in some resources-based economies is the depressed price of oil and other commodities. “Countries whose revenue largely relies on commodity exports have suffered significant budget declines by having borrowed on the basis of much higher commodity prices, which gives rise to political instability and policy uncertainty,” says Jenkins, pointing to recent legislative changes to the Democratic Republic of Congo’s mining laws and Nigeria’s Petroleum Bill as active examples.

“When commodity prices are very high that brings a semblance of balance and when they are very low everybody adjusts their positions and expectations accordingly,” he adds.

Developed world central bank policy may also have indirect credit risk ramifications. “Rising interest rates in developed markets could cause a capital flight from emerging markets,” says Simpson. “If returns become more attractive at home, companies will ask: ’why invest in tricky places?’”

Some economies in Africa are also facing a lack of access to hard currency, meaning bills are not being paid. This, combined with a potential investor capital flight and depressed commodities prices, could significantly increase the risk of non-payment in these countries, she says, explaining that there is often a lag time between a political risk event and the subsequent uptick in non-payment.

Financial protection

Against this backdrop, insurers and brokers report slow but steady growth in the uptake of political risk insurance coverages – particularly those concerning credit risk. Ed Nicholson, partner, credit, political & security risks for JLT, says JLT’s political risk division has seen year-on-year growth since 1986 and he sees uptake continuing to increase globally and across all sectors.

Political risk cover has historically been the preserve of top echelon multinationals, though smaller firms with assets in-country or whose businesses rely on contracts in one or two overseas markets are also increasingly buying cover, particularly as geopolitical events grab the headlines.

Helping companies “improve their resilience in the context of unpredictable business, geopolitical and security environments are the main points of focus”, says Nicholson.

Jenkins also notes an uptick in private equity funds as buyers of political risk insurance. “It’s been a very good fit because the levels of due diligence undertaken by the sizeable private equity funds and their transparency with underwriters makes for a very powerful partnership,” he says.

But just as demand for coverage has grown, so has insurance capacity, with several carriers and investors expanding their capabilities as they see political risk as an attractive de-correlated class of business. This influx of capacity has meant wordings have become very broad.

As Jenkins points out, each new situation can breed tweaks to existing wordings based on the latest loss experiences, particularly in countries experiencing conflict.

Substantive changes were made to the wording of non-payment-type political risk coverages in the wake of the global financial crisis, and subsequent revisions were made in the 2015 Insurance Act, making this coverage more client-friendly. Given their broad scope and affordability, credit risk covers are increasingly being bought on a blanket basis and country-by-country policies are becoming less popular, sources say.

“Soft market conditions are driving the need for insurers to differentiate themselves by demonstrating both a depth of understanding of the client’s business needs and contractual clarity,” says Nicholson, adding: “In today’s market, generic content is rare.”

But while the nature of political risk continues evolves, so too has the sophistication of buyers’ businesses. “On the one hand this means that buyers can be better placed to deal with challenges that arise and on the other, vulnerability can be enhanced or arise in ways which might not have represented a cause for concern previously,” Nicholson says.

Both he and Simpson urge companies to buy political risk insurance pre-emptively rather than waiting until a crisis hits, at which time rates can become prohibitively expensive or cover may no longer be available. “Helping a client anticipate problems before they occur or deal with potential threats is increasingly important,” Nicholson says.

Risk mitigation

According to WTW, many companies are still taking a reactive, intelligence-based approach to political risk management, rather than a proactive, mitigation-oriented approach which could help them use political risk cover more strategically. Numerous panelists, it said, complained that geopolitical analysis is “often valuable but rarely actionable in the short term”.

However, WTW’s survey did suggest that leading companies are becoming more proactive in their risk mitigation efforts, from strengthening defences against growing cyber and technology risks to organising firm-wide resources more effectively, investing in intelligence analysis, proactively building relationships with governments and reducing asset exposure through joint ventures and the use of service companies.

“More people are thinking about political risk and looking at it more strategically, which is brilliant,” says Simpson, who adds that larger companies are now taking a more diagnostic approach to modelling their exposure to political risks (such as through WTW and Oxford Analytica’s political risk modelling system VAPOR).

“Political risk management is no longer just about gathering intelligence – there is pressure from boards, investors and shareholders for companies to employ quantitative analytics so that when a political risk event happens they already have a good sense of how this will impact operations on the ground,” she explains.

More companies are also recognising the need to seek out specialist advice, notes Nicholson. “The growth of the political risk consulting and private security industries mean that corporations have a wide array of choice open to them,” he says.

Indeed, insurance too can be seen more strategically, and not just a financial backstop. “Our job as underwriters is to understand what corporate clients are trying to achieve when they invest overseas and to continue to develop coverages that underpin those strategies,” says Jenkins.

For some, political risk insurance covers may still be seen as a luxury purchase – until crisis strikes, of course. But with analytic tools now available and insurance coverage broader and more affordable than ever before, there is little excuse for failing to to act early in an increasingly unpredictable age.

No comments yet