Companies are struggling in their fight to protect IP. Their risk managers can help, says Andrew Leslie

There will have been champagne glasses raised among the ranks of copyright holders and intellectual property theft investigators on 17 April this year. This was the day that a Swedish court delivered its verdict on four owners of the notorious BitTorrent website ‘The Pirate Bay’, finding them guilty of facilitating access to copyright-protected files, and sentencing them to a year in prison and a $3.6m fine. Equally, the court threatened one of The Pirate Bay’s internet service providers (ISP), Black Internet, with a large fine unless they blocked access to the site. Black Internet complied.

For six years, The Pirate Bay had been defying the best efforts of organisations from Microsoft to Warner Bros to enforce their copyright, and publishing their threatening e-mails on the site, complete with ribald responses. Meanwhile, an estimated 23 million users had been taking advantage of the site’s tracker and index to access copyright music, film and video held by other users through peer-to-peer (P2P) file sharing protocols. Now, at last, The Pirate Bay had fallen foul of the law.

Pirates at bay?

But of course the story does not end there. The Pirate Bay was back up and running within a fortnight. Meanwhile, an appeal has been lodged, which will be heard on 9 November.

At the heart of the case lies the real dilemma facing owners of intellectual property in the internet age. Given the rank impossibility of pursuing 23 million individuals, copyright holders focus their efforts on ISPs and sites such as The Pirate Bay. But these argue that since they hold none of the copyright material themselves, this is akin to pursuing a post office merely because it delivers a parcel which turns out to contain illicit material. And questions of censorship and privacy of personal data inevitably arise – making courts and regulators tread extremely carefully.

For example, the consultation document put out by the UK’s Department for Business Enterprise and Regulatory Reform (BERR) in July 2008 ran to no fewer than 65 pages, and was hedged around with cautionary notes, best summed up by the phrase: ‘No regulatory option is straight forward. There is a complex legislative environment already in place here including privacy, eCommerce and copyright laws.’ At that point, the UK government’s preferred option was, inevitably, self-regulation and a code of practice.

A subsequent speech by the Minister of State for business, innovation and skills, David Lammy, in May 2009 continued to make it clear that a consensus was going to be difficult to reach: ‘And as with any issue that is important to people, passions tend to run high and agreement can be elusive.’

By August 2009, the UK government had bitten the bullet and realised that there would need to be legislation. Although it is still consulting over its proposals, it announced that it was considering giving its telecommunications regulator, OFCOM, powers to make ISPs send notifications to subscribers that copyright holders alleged they were infringing rights, and to monitor the number of notifications each subscriber was associated with. Thereafter, with a suitable court order, copyright holders might have access to this data.

It also proposes to give OFCOM the power to force ISPs to implement ‘specified technical measures’ (the slowing of broadband transfer speed has been mentioned as an example) against repeat infringers, with the possibility of forcing suspension of accounts as a last resort.

But, given that surveys suggest that as many as one in four internet users have accessed pirated material from the web, it is questionable whether these threats will have as much impact as the government hopes. It is obvious that not only do many people have no compunction about committing an offence that they perceive to be victimless, but a huge cultural change would have to occur before any real impact was made.

In his speech, Lammy was clear about why people resort to ripping copyright material. ‘We have seen the emergence of the “access culture”’, he said. ‘People expect to be able to find whatever they want, whenever they want it at the click of a mouse. “I want it now” means if I can’t get it legally, I’ll get it whatever way I can.’ Interestingly, Lammy suggested that the long-term solution might lie in making copyright material easily available on demand at a price that no one could quibble over paying – citing the growth of legal music-streaming site Spotify as an encouraging example.

A wider sphere

Lammy’s description of the access culture and its demands can easily be taken beyond the problems of P2P piracy to a much wider sphere. Whether it is pirated DVDs being sold in European street markets or counterfeit branded goods for sale all over East Asia, the problem is ubiquitous and unlikely to go away. When you can even buy ‘designer’ swine flu masks in Vietnamese markets, and T shirts sporting the legend ‘Music Pirate’, it is all too obvious that the chance of getting consumers en-masse to take the issue seriously is next to zero.

Conventional enforcement, and the whole gamut of patents and trademarks can help in some jurisdictions, but can be slow and expensive at best. Given the involvement of organised crime, and the unwillingness or inability of some jurisdictions to take firm steps against IP theft, it is likely that the pirates will continue to be able to dodge the copyright holders for some time to come.

Is business just as bad?

Business ought to be able to take the moral high ground. But it is not just consumers who are taking a dubious moral stance towards intellectual property rights. It is the big retailers that are driving the trend towards copycat packaging that no longer just looks vaguely similar to familiar brands, but actually mimics them so closely that, according to research commissioned by the British Brands Group, one in three shoppers has been misled into buying the wrong product.

Although they steer just clear of infringing trademark or passing off rules, producers of copycat packaging are obviously undermining their competitors’ intellectual property. The practice is blacklisted under the EU’s unfair commercial practices directive, but left in the hands of local enforcers – who may have more important matters on their hands.

The matter came to a head this August, with the news that Diageo was suing UK retailer Sainsbury for infringing IP rights after Sainsbury launched Pitcher’s – an alcoholic drink whose packaging and labelling is alleged to resemble Diageo’s Pimms brand. Ironically, Sainsbury is one of Diageo’s largest customers, and the risk of damaging their relationship with the big retail chains is one reason, according to Brand Republic, why the members of the British Brands Group are keen to retain their anonymity in their campaign against copycat packaging..

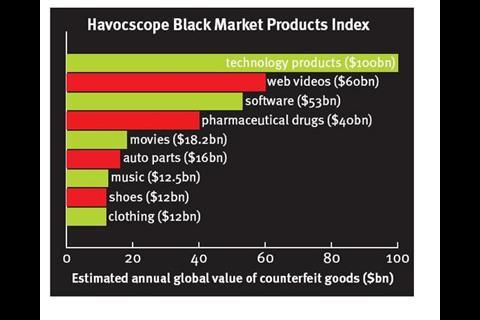

And of course, once you start looking beyond Europe, the scale of piracy and counterfeiting becomes truly mind-boggling. The Havocscope Black Markets Index estimates the global value of counterfeited goods (see above).

“The starting point is to ask what the consequences will be if a given piece of IP is stolen or abused by a competitor

What can the risk manager do?

Faced with an outbreak of disrespect for IP rights on this kind of scale, conducted by both those who manufacture and those who consume, what can a risk manager do? According to Tony Dearsley, computer forensics manager at Kroll Ontrack, the remedial work begins at home. ‘Companies don’t think hard enough about IP risk in general,’ he says. ‘But there is risk everywhere, and you have to go with the assumption that if it can be stolen, it will be stolen.’ So the first principle is to try to protect your IP by keeping it firmly in house.

The starting point is to ask what the consequences will be if a given piece of IP is stolen or abused by a competitor. Here, the risk manager has to behave like a triage nurse, and separate out individual pieces of IP into life-threatening, damaging or relatively harmless. Is there mission-critical data? Could a project, or even the company itself, be terminally damaged? In such cases, Dearsley considers that applying a ‘need to know’ regime is vital. His own take on the access culture is that the speed and ease of the information highway within organisations has led to everyone thinking they have a right to every piece of information. ‘If you go back 20 years or so, it wasn’t like that,’ he says. ‘Sure it slows things down, and perhaps there are added costs, but you have to balance business needs against security – against losing the data.’ It is a struggle, he says, between accountancy and fact.

A further necessary step, says Dearsley, is to educate your own staff and managers. In his experience, many people have no concept of the value of their own data. A series of internal memos is no substitute for someone standing in front of you explaining why security is really needed, and why intellectual property can be an organisation’s greatest asset.

Is it any use resorting to law? Yes, says Dearsley. It is not cheap, but it is effective – at least in the UK. And in that final phrase lies a further problem.

Outsourcing

In the excitement of the cost savings that are going to be achieved by outsourcing, the risk to intellectual property may barely be considered. Writing for Venture Outsource in 2007, Michael Bielski summed up why your outsourcing partners may put your valuable data at risk. They may:

* not fully understand IP, and the importance of IP rights

* be unclear with regards to your company's position regarding IP

* begin to understand your company's technology as well as you do

* develop invention(s) around your company's technology space

* not have an incentive to assist with IP issues around this invention

* reveal your company's proprietary information to please other customers they perform work for

* not have loyalty to your organization.

The crucial step in protecting your IP against the risks of outsourcing is to decide what NOT to outsource. This requires the product or process to be carefully broken down, and for those parts which add value, or serve as clear differentiators from rivals to be kept in house, despite the additional costs involved. It is also important that no part of the process to be outsourced can be reverse engineered.

Bielski also recommends making the likelihood of being able to enforce your IP rights an important part of deciding where to outsource. It may well repay the extra costs if your outsourcing can be done within jurisdictions where the law is clear and enforcement relatively easy. He also suggests – especially in the case of innovative products or software, that a team gets together to brainstorm what possible improvements or developments can be made. Steps can then be taken to protect such developments before any outsourcing contract is drawn up.

Increasing sharing

Finally, it is worth considering whether there may not be an opportunity in deliberately putting some pieces of IP into the public domain. A strand of opinion within the music industry holds that the availability of ‘free’ tracks can create a loyal fan base, who may then wish to pay to build up their collection. Apple’s decision to release a software development kit for its iPhone, allowing third parties to create applications for the product, is widely held to have massively increased the versatility and attractiveness of the product, while allowing both Apple and the developers to benefit financially.

If there is a way in which you lever the creative power of your customers to help improve your product through deliberately releasing parts of your IP, why not take it? It outwits the pirates, does your reputation no harm, creates loyalty, and turns customers into genuine stakeholders who will be on your side rather than against you in the continuing competitive struggle which surrounds IP.

No comments yet