Cyber crime is becoming increasingly sophisticated, and increasingly malicious

On 2 November 1988, 22-year-old Cornell University student Robert Morris released an internet worm capable of exploiting vulnerabilities in UNIX operating systems, infecting an estimated 10% of the internet. Over 20 years on, the scale of computer crime has grown astronomically. Internet attacks today are organised and designed to steal information from consumers and corporations.

The scale of global cyber criminal operations has reached such proportions that internet security firm Sophos discovers one new infected webpage every 4.5 seconds – 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. In addition, Sophos is sent some 20,000 new samples of suspect code every single day.

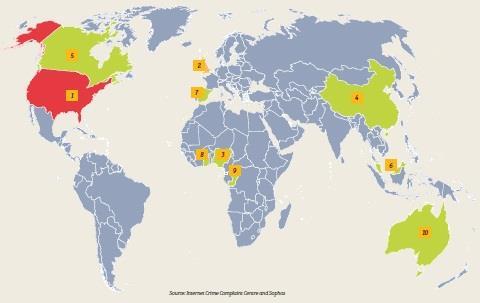

The USA, China and Russia account for almost three-quarters of the world’s websites that spread malware, according to research by Sophos. The US tops the chart, with just under three in every eight infected webpages based there. China, which was responsible for hosting more than half (51.4%) of all the world’s malware in 2007, has now almost halved its contribution to the problem.

The Czech Republic is a new entrant on the list and hosts over 1% of all the world’s malware. Poland, France, Canada and the Netherlands were in positions six, eight, nine and 10, respectively in 2007, but now have too few malicious websites to appear on the chart.

No one is immune

A number of well-known organisations have fallen foul of malware, including thousands of websites belonging to Fortune 500 companies and government agencies, which were infected in January 2008.

Traditionally done through emails, cyber criminals now primarily use the web to infect computers, often driven by political motivations. Immediately before releasing a series of leaked diplomatic cables, Sweden-based WikiLeaks (the whistleblowing website) suffered several distributed denial of service (DDOS) attacks, which succeeded in putting the website temporarily offline.

In an apparent act of revenge, sites that had refused to support WikiLeaks were targeted in return, with Mastercard briefly being forced offline and Amazon also targeted. The ‘hacktivist’ group Anonymous, which had previously mostly confined its actions to anti-pirate organisations and the Church of Scientology, was widely believed to have had a hand in these attacks, dubbed ‘Operation Payback’.

No comments yet