Youth unemployment has reached staggering levels, and disaffected young people can trigger many more risks

Open publication - Free publishing - More atlas

Figures released in January show that youth unemployment in Spain reached 51.4% among those aged 16 to 24. A shocking one in two young people in Spain is without a job.

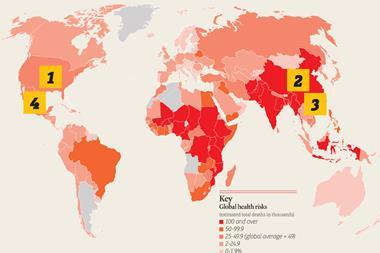

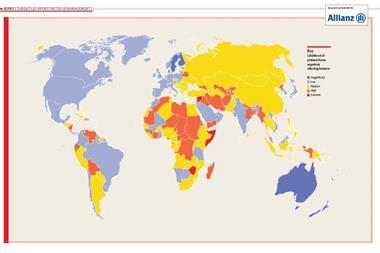

As the Risk Atlas shows, the situation is not much better in several other parts of the world. High rates of joblessness among young people is a risk that can easily be correlated with other social problems, such as civil unrest, drug use and crime. The collective frustration among youth has been a contributing factor to protest movements around the world this year, as it becomes increasingly difficult for young people to find anything other than part-time and temporary work.

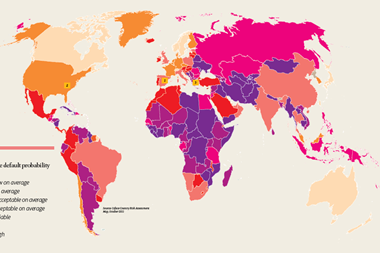

High rates of joblessness among young men was certainly a factor in the Arab Spring uprisings that continue to sweep across the Middle East. Going back further, after the financial crisis in Argentina in 2001, which led to the collapse of the Argentinean economy, large numbers of young people became addicted to the drug Paco (short for ‘pasta base de cocaine’ – a substance created at the early stage of cocaine production). The highly addictive and cheap drug expanded out of the ghettos to the Argentine middle class. No definitive numbers exist on deaths.

Youth unemployment was high on the agenda at the World Economic Forum in Davos, where politicians, economists and bankers said action was essential to stimulate growth and prevent a ‘lost generation’. This is set against a backdrop of rising frustration among millions of young people worldwide who are facing high unemployment, increased inactivity and precarious work.

As recent figures show, the global economic crisis has led to a substantial increase in youth unemployment around the world. And it’s not just a problem confi ned to poorer countries. At the peak of the crisis period in 2009, the global youth unemployment rate saw its highest annual increase on record, going from 11.8% to 12.7% between 2008 and 2009 – an unprecedented increase of 4.5 million unemployed youth worldwide. The average increase of the pre-crisis period (1997-2007) was less than 100,000 young people per year.

A report from the International Labour Organisation (ILO) on youth unemployment in January said: “For the generation entering the labour market in the years of the Great Recession, there is not only current discomfort from unemployment, under-employment and the stress of social hazards associated with joblessness and prolonged inactivity, but also possible longer-term consequences in terms of lower future wages and distrust of the political and economic system.”

Executive director of the ILO employment sector José Manuel Salazar-Xirinachs said that ultimately the job market will only ever pick up if “obstacles to growth recovery” are removed, “such as accelerating the repair of the financial system, bank restructuring and recapitalisation to re-launch credit to small- and medium-sized enterprises, and real progress in global demand rebalancing”.

As with every risk, there’s an upside too. Countries and companies that are still in a position to offer employment should easily be able to attract the best workers.

Chancellor Angela Merkel only had to mention Germany’s shortage of healthcare professionals at a recent European summit to trigger an influx of migrant workers from Spain into her country. Those companies that are still growing should, similarly, be able to pick and choose from a large pool of talented and enthusiastic young people.

No comments yet