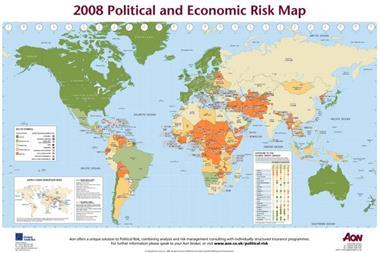

A report on political risk finds that the battlegrounds of the war on terror continue to dominate global risk trends

In an increasingly unstable world, knowledge about threats that lie ahead is far from certain.

Last year, several parts of the world felt the force of violent attacks that posed threats to businesses and disruption to global trade routes.

There were attempted car bombings in London as well as a deadly strike at Glasgow airport. The troop surge in Iraq seemed to be having its desired effect, but the security situation in Afghanistan continued to deteriorate. Meanwhile, fighting along the border with Pakistan intensified and the world took note when popular opposition leader Benazir Bhutto was slain. Around the same time, a sharp rise in commodity prices sparked social unrest in almost all regions of the globe.

One source, Exclusive Analysis, recently released its political risk predictions for the year ahead. The report found that the battlegrounds of the war on terror continued to dominate global risk trends.

Nevertheless, according to one of the authors, despite a significant jihadi extremist presence in Waziristan (the Pakistan-Afghanistan border), al-qaeda is unlikely to have a network in the region sophisticated enough to launch another 9/11 scale attack.

One reason for this, said Kirsten Parker, director of analysis at EA, is the Waziris penchant for short term alliances and tribal relationships—these local influences constrain the ability of foreign jihadis to act.

‘While al-qaeda may be treated as guests they do not have extensive networks or free reign,’ she said.

Video messages from al-qaedas leaders, like Al-Zawahiri, are reactive rather than proactive and give little indication of possible attack scenarios, revealed EA.

Parker added that the result of Pakistan’s general election—expected to end in a three party coalition government—is unlikely to have much of an affect on levels of domestic violence, because tribal groups remain disengaged from the political process.

Despite the complexities of operating in this environment, western self-radicalised extremists often travel to the region to learn terror tactics at graduation camps. These camps, said Parker, are nothing like the pre-9/11 complexes and more often than not serve only to alert western security forces of the would-be-terrorist.

Therefore the threat of home-grown extremism in the US remains low, said the firm in its report, because the groups are unsophisticated and often clumsily reveal themselves to intelligence authorities. Conversely, in the UK—while the numbers of people being arrested has remained steady since 2006—techniques continue to be refined. Parker pointed to the liquid explosives plot in 2006 as an example of this.

Elsewhere, expatriate kidnappings in Nigeria sky rocketed in 2007—with an average of six or seven major incidents each month in the Niger Delta alone, according to EA’s figures. ‘There are lots of structural reasons to believe this level of threat will continue,’ said Parker, who added: ‘The army tend to do badly against the militants who know the terrain and are part of local communities.’

The threat posed by state control over natural resources in Russia continued as a theme in the report. Putin’s desired successor is likely to continue with the practice where business feeds into the activities of state, found Parker. ‘Foreign businesses are likely to have limited influence in the region,’ she said.

No comments yet