Sean Lyons asks to what extent the corporate world is preparing itself for defending the interests of all its stakeholders

The term “Corporate Defence” has been in use over a long period of time, has a wide range of common usage, and has been used in many different contexts. As a result while it is perhaps intuitively understood, its precise meaning can differ from person to person and its precise definition can therefore vary depending on the circumstances in which it is applied. Examples of activities which use this term include areas such as legal, security, resilience, governance, risk, compliance, audit and investigations. The term is even used when defending against hostile takeovers. Each of these usages shares the common high level objective of defending the organisation, and therefore could be said to represent different lines or multiple layers of defence. Corporate defence therefore in its broadest sense could be said to represent an organisation’s program for self defence.

Let us briefly compare corporate defence to the concept of “National Defence”. With national defence the post of minister or secretary of defence is generally considered to be a senior cabinet position, reporting to the Prime Minister or President. The minister or secretary of defence has responsibility for managing the ministry or department of defence. The ministry or department of defence in turn generally has ultimate responsibility for formulating defence strategy and policy, and for integrating policies and plans in order to achieve defence objectives. All defensive activities, including Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corp etc ultimately report to this department or ministry while still retaining responsibility for tactical planning and for on the ground implementation and execution. This allows for the strategic alignment of all defence related activities while also (if competently applied) facilitating the tactical co-ordination and operational integration of these activities. The key issue which this paper seeks to address is to what extent the corporate world is preparing itself for the adoption a similar approach towards corporate defence and defending the interests of all of its stakeholders? By stakeholders I am referring to all those parties with a vested interest in the organisation.

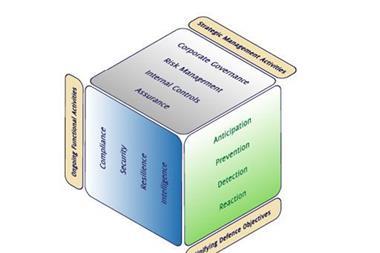

In an attempt to safeguard against risks, threats and vulnerabilities most organisations have already introduced a multitude of specialist functions. The corporate defence domain represents these different defence related activities, all of which contribute to the defence of the organisation. The following represents an example of activities which make up what can be described as the corporate defence domain.

The corporate defence domain (see Figure 1)

As a result of events at Enron, Worldcom and more recently Societe Generale, a growing number of business analysts and industry experts are now thinking outside the box in this area and beginning to acknowledge the critical interdependencies which exist between these activities. The corporate defence domain is therefore increasingly being seen to represent a defence ecosystem, as there is a growing appreciation of the symbiotic relationships which exist between these activities. Increasingly corporate defence is now being regarded as representing an asymmetric challenge for an organisation, as a point in time weakness in any one of these activities can be exploited resulting in a destabilising consequence throughout the organisation. From an operational perspective perhaps the single greatest challenge therefore facing organisations is to ensure that the management of these defence related activities is effectively unified, aligned and integrated.

Functional developments in this area

Over the last number of years in particular there has been significant developments in each of these defence related activities, so much so that it has been described as an evolutionary process which appears to be occurring in predictable phases. This evolutionary process seems to be occurring in practically all of the activities previously mentioned, although some are at a more advanced phase of maturity than others. For the purpose of this paper we will look at these developments in terms of a maturity model and the likely business impact derived at each stage of maturity. This maturity model of which there are many variations is based on an adaptation of the capability maturity model (CMM) which was developed for defence software purposes by the Software Engineering Institute (SEI) at the Carnegie Mellon University in the mid 1980’s (Humphrey 1989). Derivatives of this maturity model can be found in practically all of the defence related activities previously referred to.

Phases of development (see Figure 2)

The disparate phase

Initially each individual business unit tends to be left to their own devices in developing its approach or methods in relation to any one of these defence activities, and this could therefore be said to represent something of a disparate or fragmented type approach. The business impact associated with this phase of development is considered minimum as the activity tends to be performed in an ad-hoc manner and can often result in a crisis management mode whereby the business unit is continuously fire fighting on a day to day basis. At best there is typically a “to the letter of the law and no more” attitude in place. The processes adopted by the individual business units and the methods applied are usually not documented and therefore not consistently repeatable. These processes are subject to change based on the individual responsible or the event encountered. In general the processes are developed without the required level of planning, tend to be manually intensive and thus time consuming, and lack the required degree of formality to enable the process to be repeated successfully. As these activities are not coordinated but left to the business units to address individually, the organisation as a whole does not have a stable or consistent approach in relation to this particular defence activity, and many areas may not know, be aware of or sufficiently understand the necessary components required to help ensure a stable approach. Consequently the success of this activity can typically depend on the knowledge and competence (some would say heroics) of individuals and the level of team member efforts within the business unit.

The centralised phase

The activity next tends to become consolidated into a centralised function, which requires specialist skills and expertise. This phase could be described as 1st generation convergence, pulling disparate activities together under one umbrella, using a centralised type approach. The business impact associated with this phase of development is improving but is still considered to be limited. The activity is now seen as a specialist area and is considered a defined professional discipline within the organisation. The centralised function now has responsibility for implementing and developing requirements, and this involves developing a structured approach, and requires appropriate documentation in order to help to ensure that the process becomes repeatable, whereby consistent results can be expected. At this phase the process discipline itself is unlikely to be thorough throughout the enterprise however when these principles are applied in practice, the activity can be performed in accordance with documentation.

The enterprise-wide phase

The next phase of development is a push to embed these specialist principles throughout the organisation or on an enterprise-wide basis. The business impact associated with this phase of development is now considered to be increasing to reasonable. The organisation now agrees on its enterprise objectives and to a defined set of methodologies which are required to be the standard or benchmark for a particular activity. These standards will form the basis of a consistent application of this activity throughout the organisation and these strategies, policies and procedures are used to help to educate the entire organisation. In order for this to occur there is typically an element of decentralisation involved in this approach whereby line-management is responsible for ownership and ensuring that these standards are appropriately applied. At this level the standards, process descriptions, and procedures for the activity are tailored where possible to suit a particular organisational unit’s individual circumstances. This level represents a move towards a more sustainable approach to the defence activity involved, as the organisation now knows exactly where it needs to go, knows how to get there, recognises the need to build the activity into their operational processes. The organisation is now focused on ensuring that these standards are embedded into culture of the organisation.

The integrated phase

The next phase, the integration phase, is now possible as a result of advances which have been occurring in technological solutions. This involves moving towards an end-to-end vertical and horizontal integration of a defence activity using technology. The business impact associated with this phase of development is now considered advanced. This integrated approach is the natural progression from the enterprise-wide approach where the activity is now integrated into all operational processes enabling management to effectively control the activity by migrating from a manual to an automated control environment. The organisation now has fully integrated reporting in place for this activity and has now determined its essential measurement metrics. This means that goals now become quantifiable and therefore performance becomes more predictable. Using these measurement metrics, management can now begin to anticipate and evaluate the activity’s performance in totality. Management can now determine methods to modify and amend the activity to particular circumstances without significant reductions in quality or divergence from its defined benchmarks.

The optimised phase

The final phase, described as the optimised phase, focuses on deliberate process improvement and optimising the use of the organisation’s resources. This is possible because the organisation now has it people, processes and systems fully integrated, and its workforce has now become empowered. The business impact associated with this phase of development represents the organisation’s opportunity to deliver maximum impact. By constant efforts at continuous improvement and by adopting accelerated learning techniques, the organisation helps ensure that processes are continually enhanced and that performance becomes more innovative. This phase involves continually improving process performance through both established and pioneering improvements. Quantitative and qualitative improvement objectives are determined, continually revised to reflect changing business objectives, and used as benchmark criteria in managing improvement. Both the defined goals and the organisation’s set of benchmarks are targets for constant evaluation and assessment. The effects of the organisation’s efforts to improve activities are now assessed and evaluated against the quantitative and qualitative improvement benchmarks. Optimised processes are flexible, adaptable and innovative, dependent on the participation of an empowered workforce, and the alignment with business values and the objectives of the organisation. The organisation’s ability to rapidly react to changes and identify opportunities is enhanced by finding ways to accelerate learning and share knowledge. At this phase, business processes are concerned with addressing root causes of process exceptions, variations and anomalies, and continuously adapting its processes in order to constantly improve business performance and productivity.

While there certainly appears to be a great deal of activity occurring in each one of these defence related activities, if one were to adopt a more high level strategic view certain observations can be made in relation to these functional developments. What begins to become clear is that all of these activities now appear to be moving in a similar direction, and therefore they are all encountering similar challenges along the way. It becomes apparent that all share a common high level objective, which is ultimately to safeguard the organisation, however in many of the more traditional style organisations these activities tend to operate in silo or stovepipe type structures, whereby these activities are not in alignment with one another but rather they are operating in isolation.

Cross-functional developments

In an attempt to address these silo type issues, similar developments are now also occurring at a cross-functional level. What is now emerging is an evolution in cross-functional convergence, in what could be referred to as 2nd generation convergence in this area. These cross-functional developments represent a reaction to the functional silo type environments which have developed over time within organisations, and an attempt to reduce the resulting overlaps, duplications and redundancies. The following represent some significant developments which have been occurring in these sectors.

RISK MANAGEMENT

Developments in “Operational Risk Management” (ORM) are seen by many as perhaps the most significant development in the evolution of contemporary corporate defence. For the first time ORM represented a formal recognition of risks other than market and credit risks. ORM focused attention on the existence of operational risks and addressing these risks in a disciplined and systematic manner. It represented official recognition of the need to address operational risks in a formal way, rather than the ad-hoc manner which had previously been employed. In many organisations however the role of ORM has been somewhat superseded by “Enterprise Risk Management” (ERM). There are many reasons for this but it appears that it primarily has to do with the issues of status and authority within the organisation. The development of the ERM framework was designed to embed risk management principles and procedures throughout the entire organisation. This promotion of a risk management culture was an attempt to help ensure that all areas within the enterprise would adopt a risk based approach and focus on the identification, measurement and management of risks. More recently there have been attempts to introduce integrated risk management systems into many organisations, however in truth these attempts are currently still in their infancy. The following represent cross-functional developments which are seen as being risk management driven.

OpRisk and compliance

Currently we are seeing attempts by some organisations to introduce a union between the organisations’ operational risk issues and its compliance obligations. This union has been termed “OpRisk & Compliance” and has recently seen the “Operational Risk” magazine being renamed the “OpRisk & Compliance” magazine. This union perhaps reflects the increasingly onerous operational compliance requirements which organisations are now facing and the increasing overlap between compliance and risk management.

Risk intelligence

Risk intelligence represents a fusion of risk management and corporate intelligence. Its objective is to help ensure that an organisation can make faster, better, more informed business decisions, in terms of dealing with the risks it is faced with. It is concerned with making better use of the information an organisation already possesses. How organisations cope with risk and how they develop their risk intelligence determines their competitive advantage in terms of their competition. It has been described as an organisation’s ability, compared to its competitors, to assess a risk, and it depends on an organisation’s informational advantages and how these advantages are applied (Apgar 2006). Its premise is that organisations with low risk intelligence tend to be continually in a reactive mode and will tend to face far more unwelcome surprises going forward.

COMPLIANCE

In recent times the building of a culture of compliance within an organisation has become a business imperative in the boardroom. The board’s role in the oversight of an organisation's compliance program is increasingly under scrutiny and it is considered vital to the long-term success of the organisation. Increasingly organisations began to appreciate that an effective compliance program requires enthusiastic support from the board and senior management, in addition to an organisation-wide commitment. To be successful a compliance program requires effective systems of training, communications and controls throughout the enterprise. The following represents cross-functional developments which are seen as being compliance driven.

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act 2002

In the United States the introduction of the Sarbanes-Oxley act in 2002 imposed legislation which has had a significant cross-functional impact, not only as a regulatory compliance issue but it also has specific implications regarding organisations’ approaches to corporate governance, risk management, internal controls and assurance. This legislation (particularly sections 301, 302 and 404) is seen as a regulatory attempt to defend the interests of the stakeholders with a broader corporate defence perspective in mind. The subsequent modification of the relationships between executive management, financial control, internal and external auditors, and the audit committee was certainly designed with the intention of introducing a more robust system of checks and balances within the corporate framework.

Governance, risk and compliance (GRC)

The arrival of “Governance, Risk and Compliance” (GRC) represents the coming together of corporate governance, risk management and compliance (OCEG 2007). It represents the recognition that these activities share a number of common objectives and can result in the occurrence of a considerable degree of intersections, overlaps and duplications throughout organisation. For this reason many business analysts believe that the concept of a cross-functional convergence of these activities represents a progressive approach in this area, and is quickly replacing the traditional fragmented or silo mentality. By adopting technology platforms which help to unify the management of “Governance”, “Risk” and “Compliance”, organisations can hope to overcome the problems caused by business fragmentation and disjointed approaches in these areas. Acknowledging the requirement for even further cross-functional convergence in this sector some GRC vendors are already offering additional functionality in the areas of operational controls, assurance and security, which were perhaps previously considered as being outside of the scope of governance, risk and compliance.

INTELLIGENCE

In an effort to introduce a standard business intelligence (BI) environment we are now hearing terms such as “Enterprise Business Intelligence” (Eckerson & Howson 2005). This represents an effort to standardise strategies, techniques and tools in order to help educate organisations on how to design, build and maintain both information systems and knowledge management practices. The goal is to empower users by giving them direct access to information in order to help them make better decisions. By streamlining the use of technology by the consolidation of purchasing, it is possible to reduce the number of vendors used, thus helping to standardise the tools in operation. By evaluating the scalability, performance, and suitability of technology solutions before deploying them on an enterprise-wide basis, over time it is becoming possible to transform it from a departmental to an enterprise initiative. Responding to business needs leading vendors are now developing and providing BI solutions that consist of integrated suites running on common application services and platforms. These can be customised to meet the information and analytical requirements of large numbers of individuals and groups.

As more and more companies now begin to appreciate that intelligence represents the life blood of an organisation, intelligence is becoming more and more integrated into all of the other defence related activities. Increasingly we are now seeing developments in a number of areas including “Risk Intelligence”, “Compliance Intelligence” and “Assurance Intelligence” etc, and we are now hearing the term IQ being applied more and more in practically all of the defence related activities previously referred to. The emerging term IGRC is now being used by a number of vendors to describe the critical link between intelligence and governance, risk and compliance (GRC), thus acknowledging the relationship which exists between all four activities.

End of Part 1...continued in Part 2

Postscript

Author: Sean Lyons

Risk-Intelligence-Security-Control

R.I.S.C. International (Ireland)

sean.lyons@riscinternational.ie

www.riscinternational.ie

No comments yet