How would insurance policies respond to injury claims following a nuclear, chemical or biological attack? Robin Ferguson says there is a need for greater clarity

Increasingly, we live in a world where it is not only possible but necessary to think the previously unthinkable. Before 9/11, terrorism losses on such a scale – and in particular the vast personal accident (PA) insurance accumulations that arose from the destruction of the World Trade Center – were almost inconceivable. But now the threat of major terrorist actions is something no organisation can afford to take lightly.

Group PA insurance can provide vital protection for what are organisations’ most precious assets: the people they employ. But there are currently major uncertainties surrounding the issue of whether and how UK companies’ PA policies would respond in the event of widespread bodily injuries caused by the use of nuclear, chemical or biological (NCB) agents.

It may seem anomalous in this supposed new era of contract certainty, but the majority of UK group PA carriers are steadfastly silent on the issue of NCB. Is it covered or isn't it? Next question please! Thus far, UK risk managers have seemed remarkably relaxed about this lack of clarity – perhaps because it seems a minor footnote to more routine PA risks, perhaps because 'it will never happen', perhaps because their brokers lack interest in the topic.

One possible explanation is the assumption that matters left unclear in the policy wording will ultimately be resolved in the policyholder's favour. In the event of a relatively minor incident, carriers might indeed be happy to meet losses stemming from NCB contamination. But is it really plausible to suppose that major insurance organisations en masse would remain silent on the issue of NCB because they are willing and ready to pay whatever open-ended losses may eventually arise?

In reality, opting for silence leaves open a number of potential loopholes through which liability could be evaded. Resolving a claim against a PA insurer whose wordings are silent on NCB contamination, would require looking carefully at the definition of accidental bodily injury.

Would inhalation of a chemical substance constitute bodily injury? How is incident defined? Would the further-reaching consequences of a release of biological agents be covered? Depending on how war is defined, a claim could be rejected or limits applied on the basis of phrases such as 'warlike activities' or 'attempt to participate in acts of war.' There is also the question of proximate cause: would bodily injuries occurring months after the release of NCB agents be considered attributable?

Liabilities from a single building could potentially amount to billions of pounds. Given this, it seems only reasonable to suppose that all these questions – and many others – would be argued over at length in the courts should they ever arise in practice, particularly since a major NCB contamination could severely stretch the financial resources of even the largest insurers.

Something, not nothing

A policy that leaves open the question of whether NCB risks are covered is not something you can build a reinsurance programme around. So even if a carrier was willing to pay out, it might struggle to do so in practice.

“A policy that leaves open the question of whether NCB risks are covered is not something you can build a reinsurance programme around.

Openness, transparency and responsible underwriting surely dictate that is preferable to offer a policy wording that specifically covers some elements of NCB risk – rather than one which might cover something or might cover nothing.

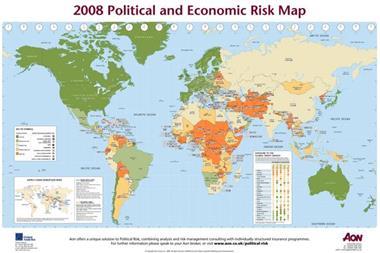

Having a specific wording in place for NCB risks makes it possible to monitor the geographical distribution of exposures at individual postcode level, to manage aggregate exposures responsibly, and to purchase specific reinsurance to cover each risk taken on – safeguarding the ability to indemnify policyholders in the event of an incident.

By their very nature, NCB terrorism risks are hard to predict and model. The range of factors that could influence the outcome of a particular event is immense and highly variable.

Contract certainty

The Polonium 210 contamination at the time of the Litvinenko poisoning could have affected over 300,000 people. Happily, apart from the unfortunate Mr Litvinenko himself, no one seems to have been seriously hurt. But it takes little imagination to see how the ripples from a major NCB incident could spread out.

Coming up with a specific wording that offers the policyholder effective premises-specific cover against NCB risks, while excluding the financially untenable consequences of contamination across a wider area, is no simple task. But in this era of contract certainty it seems the only responsible course to follow. Limiting cover to within 100 metres of the premises in question, and specifying manifestation within 28 days, claims notification within 35 days and death or disablement to have occurred within six months of the incident, seemed ultimately to strike the right balance.

Whether or not these silent policies will respond in the event of an NCB incident is something no one would wish to see tested in practice. The fundamental issue here is one of certainty versus uncertainty. Just as we cannot dispel the threat of terrorism by refusing to think about it, so we cannot manage risk without defining it. By offering risk managers the assurance of indemnification for a defined range of NCB-related losses, we are at least helping to make the world a slightly less uncertain place.

Postscript

Robin Ferguson is personal accident development manager, RSA.

E-mail: robin.ferguson@uk.rsagroup

No comments yet