Sacrificing sustainability in the supply chain to satisfy shareholder returns presents the biggest single risk to business, says professor Gail Whiteman from Lancaster University Management School

The ultimate risk to business does not manifest in market trends or technology advancements. The single biggest challenge to business, the economy and society at the present time is climate change.

Without the planet, business cannot survive. To be sustainable, global business needs genuine renewable energy sources, international commitment to lower carbon emissions, the eradication of non-sustainable supply chains and measures of value that do not simply satisfy shareholder purses.

December’s 21st Conference of the Parties (COP21), in Paris brought together 50,000 delegates from government, intergovernmental organisations, UN agencies, business leaders, NGO’s and civil society. Their objective? To commit to preventing global warming from increasing the temperature of the planet by more than 2 degrees Celsius – the point at which we can no longer avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

Perhaps it is a utopian outlook, but all of the above is possible. Some of the best, brightest and most action-orientated people come from business. However, it does all come down to risk.

The challenge is convincing global business leaders to take the risk: to challenge norms, to seek solutions and to be courageous in pioneering the changes that are so desperately needed.

How can we do this?

Speak the same language.

In order for this to happen, climate change needs to be brought into the boardroom. The challenge is to translate the hard science of environmental research into a language that businesses understand. The science needs to be communicated in a way that speaks directly to an organisation’s bottom line.

A transformation of our energy, industry, agriculture and forestry systems is needed to reverse the rise in greenhouse gas emissions and achieve a net zero emissions society in the second half of the century. Our solutions need to be as big as the challenge itself.

They need to be presented within tangible frameworks in a way global leadership teams can implement and work with. These frameworks also need to be able to facilitate key business solutions to help solve the problem.

When an international chief executive asks: “What can science tell me that will make a difference and have an impact on solving global warming – while also allowing me to scale up my business?” the answer needs to be in the language of the boardroom, not the lab. The answer exists.

There is an area of environmental research called the ‘planetary boundaries’. This model of sustainability has been researched since 2009 and was endorsed by the United Nations secretary general Ban-Ki Moon in 2012. It identifies nine ecological processes whose correct and sustainable management are pivotal in achieving climate change goals.

This diagram is hard science, yet if interpreted as the KPIs for the planet, it is immediately obvious how easy it can be to translate for implementation within a business. This model has the potential to become a dashboard for CEOs and risk managers to help them lead and manage both sustainably and, crucially for business, scaleably.

The planetary boundaries framework has already been identified as a key framework for forward-thinking companies. For example, Paul Polman, Unilever chief executive, has made the framework the lynchpin of the Anglo-Dutch company’s Sustainable Living Plan.

More broadly, the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) – a CEO-led business association and the leading voice in corporate sustainability – has also integrated the planetary boundaries framework and other scientific evidence into its new collective strategy for business solutions for sustainability called Action2020.

After developing scientific-based priorities for action – ‘societal must-haves’, Action2020 helps businesses identify key planetary risks and crucial solutions for action.

In addition, focusing specifically on climate change, WBCSD has led a ground-breaking risk management initiative on climate solutions as part of Action2020, called the Low Carbon Technology Partnerships initiative (LCTPi).

Unlike many non-ambitious governmental approaches to greenhouse gas emission reductions, the LCTPi business solutions have the potential to “deliver 65% of all the carbon emission reductions needed to meet the UN target of keeping global warming to under 2°C”.

LCTPI could also deliver significant benefits to the global economy and importantly create jobs… and, of course, help to save the planet.

Challenge

What other companies are leading the way? An example of an organisation that has demonstrated commitment to sustainability, while being successful, is the Pentland Group. The sports brand management group is an early signatory to the UN Global Compact. In an industry tarnished by stories of Bangladeshi sweatshops, the Pentland brand is synonymous with heritage and sustainable growth.

Speaking at the launch of Lancaster University’s Pentland Centre for Sustainability in Business, Pentland Group chairman, Stephen Rubin highlighted several things that companies could do to push the boundaries of sustainability, all of which can be summed up in one action – challenge. Do suppliers (throughout the chain) ensure maximum efficiencies in water and energy use? Are they active in sourcing the sustainable sources of raw materials? Is every opportunity explored when seeking to close the loop and bring recycled materials back into the chain?

According to Rubin: “The biggest and most important question lies in the seeking of new ways of doing business. What if, in the future, nobody bought shoes, but rented them, as we do with ski boots?

“Can we consider an idea where companies are taxed on the amount of raw materials they use in production? What if recycling was incentivised by tax breaks?”

Courage

The one quality needed to challenge current thinking is courage.

Lack of courage brought about the banking crisis in 2007 and lack of courage meant that millions of cars rolled off the production line at Volkswagen last year without anyone flagging that they were breaking emissions standards.

But what does courage look like? What is the difference between being courageous and taking risks?

Peter Bakker, WBCSD president and chief executive, argues that courage lies in the redefining of corporate values. New business models that place value on societal and natural impact are emerging and flourishing.

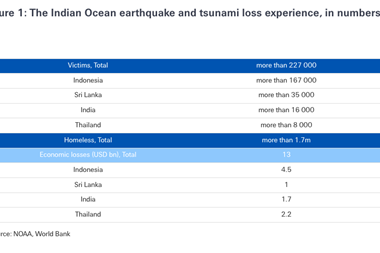

Social enterprise Gandys Flip Flops, founded by two brothers following the loss of their parents in the 2004 Indian Ocean Boxing Day tsunami, is “fuelled by giving back”.

As well as launching a successful clothing brand, the organisation funds children’s homes in India and Sri Lanka with a long-term aim to open them around the world.

In addition to emerging and developing social enterprises, companies such as Uber and Airbnb are changing the traditional supplier/consumer relationship and opening up and growing the sharing economy. Instead of being viewed as threat, organisations should be seeking to collaborate and learn from these pioneering companies.

Courage also lies in leadership. The leaders at COP21 have committed to keeping global warming at below 2 degrees. But how? Bakker, a native Dutchman, refers to the old English meaning of the word leadership to answer this question.

The origin of the word leadership literally means ‘pathfinder’ and he believes it is the responsibility of the leaders at COP21 to find the path to sustainability. He points out the path to sustainability is signposted: innovation, valuation, collaboration and courage.

The threat posed by climate change is real and cannot be ignored. It poses risks to human resources, natural resources, supply chains, and food chains.

My work as an academic is seeking to close the gap between science and business so leaders are given the tools and knowledge afforded by science to make the courageous decisions to initiate change.

Equipped with tangible, achievable KPIs for the planet, global leaders can be mobilised to action geared towards a sustainable future.

Leaders such as Stephen Rubin and Peter Bakker are pioneering the way to this future by pushing boundaries, asking questions and seeking new ways of doing things.

What is needed is leaders and managers to join them and others in making courageous decisions about sustainability. Challenging norms, seeking solutions and pioneering change are risks we all need to take.

No comments yet