Recent research shows that most companies will face a value destroying catastrophe at least once every five years. Here two experts show how responding well to one can actually help boost the value and reputation of your company

Natural catastrophes, terrorist attacks and system breakdowns, these are among the events that are almost impossible to anticipate and extremely difficult to cope with.

Unfortunately they happen very often. Eight out of ten large companies will face a major crisis that knocks 20% off the value of their compnay at least once every five years, according to respected research.

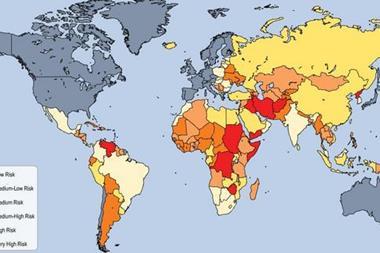

You only have to look as far back as March when a huge earthquake triggered a tsunami that devastated north-east Japan, crippling businesses around the world. Or this month, record breaking floods in Thailand have had a similarly harrowing effect on corporate supply chains.

Black Swans, rare but devastating events that come from the unknown, are happening with increasing frequency. To effectively respond to and recover from these extreme events there are plenty of things businesses need to remember.

Successful risk management requires companies to anticipate, prepare for and mitigate the impact of these extreme events.

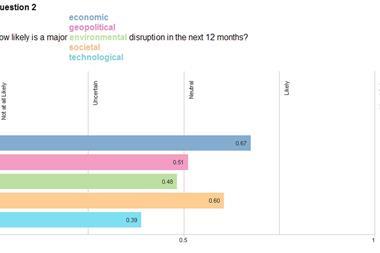

Rod Ratsma, head of Marsh’s business consulting practice, thinks it’s easy enough to predict the likelihood of a major crisis occurring, but much harder to estimate it’s impact on your business.

“Likelihood is a mathematical concept,” he says. “I can tell you precisely what your chance of winning the lottery is tonight, and I can estimate the likelihood of your factory burning down by looking at past insurance records. But only you as an individual can decide whether the risk [or impact] is high or low.”

Estimating the wide-ranging impact on your business from a tsunami in Japan or a flood in Thailand is fraught with difficulty. It requires a fluent understanding of business processes, systems and interdependencies. As well as visibility deep into the supply chain.

The trouble is that it’s tricky to know the impact of something before it has actually happened.

The best defence against these types of catastrophe risks is a well diversified supply chain, with plenty of easily identifiable alternative sources of supply. But that’s not always easy to achieve.

So says Ratsma: “Get your components from more organisations in different parts of the world and you can mitigate the risk of a natural catastrophe having a devastating effect on your business in a particular area.”

More often than not, though, businesses are unable to influence whether or not a crisis occurs. But they do have to pick up the pieces afterwards.

As Dr. Deborah Pretty, principal of Oxford Metrica, explains: “Be it natural catastrophe risk or that of terrorist attacks, both involve sudden, exogenous shocks to the corporate system and management is responsible not for the cause itself but for the firm’s response to it.”

Crisis management is delicate and complex. Dealing with the aftermath of an extreme event is logistically challenging and sometimes emotionally traumatic for any business’ senior management.

If an incident occurs, its effects on market share and reputation can be turned into something positive if the management shows strong leadership and handles the crisis well.

In the study cited above the analytics firm Oxford Metrica proved how the sensitivity with which management responds to crisis events may often inspire confidence in investors and add substantial value.

“The awareness of what managerial decisions and behavior are required, and the courage to act accordingly, reveals qualities in managers appreciated by the markets,” says Pretty.

Extreme events sometimes lead investors to review their opinion about a firm’s management. If the crisis management demonstrates good communication strategies and strong leadership it will win renewed trust from investors and sustain shareholder value.

No comments yet