This year’s hurricane season devastated the Gulf of Mexico, but the ensuing supply chain disruption will be felt the world over. In an age of interconnectivity, supply chain visibility and continuity planning has never been more important

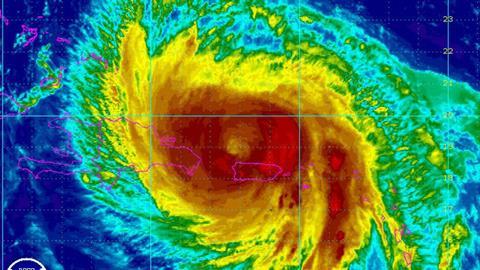

Insurers were quick to release loss estimates in the wake of the devastation reaped by Hurricanes Irma, Harvey and Maria (pictured), but the impact of the implications for supply chains around the world will take many months, possibly years, to be fully realised.

“Supply chain risk reveals itself in multiple waves. After the initial disruption there is then second and third tier disruption, and the numbers can get astronomical,” says Sarah Sherman, property practice leader at JLT Specialty USA.

Catastrophe risk modelling firm RMS estimated that economic losses from Irma will be $35-50bn in the US and $25-45bn in the Caribbean, adding to the $30-60bn Maria cost the Caribbean (primarily Puerto Rico) and the $70-90bn Harvey cost the US a fortnight earlier.

RMS estimates around 70% of these losses will be covered by insurance in the US compared to less than half in the Caribbean.

“Insurance doesn’t solve the problem, it just pays out on a loss. Companies’ top priority right now is to get back to business rather than collecting claims,” says Sherman.

While the brunt of business interruption will initially be felt in the US - Port Houston facilities generated $215.9bn for the US economy in 2016, supporting 2.7m direct, indirect and related jobs - ripples from the disruption will be felt all around the world.

“All industries have the potential to be impacted, in any location, due to the interconnectivity of supply chains and the cascading impact hurricanes can have,” says Ken Katz, property risk control director at Travelers.

Hurricane Harvey reportedly disrupted or shut 13 refineries, causing offshore oil production to drop by as much as 22% and gasoline prices to spike by 50c per gallon. According to risk intelligence platform Adapt Ready, seven billion barrels of fuel were stranded due to port closures, causing weekly losses of $11bn on Texas’s Gulf Coast.

Fuel shortages were also reported in Florida, while agricultural production was also severely affected in Florida and North Carolina.

Puerto Rico felt Maria’s full force and its economy has been brought to its knees, with power providers estimating the whole island will face power shortages for the next six to 12 months. Business losses on the US mainland could potentially have been even worse if Maria’s path had shifted towards manufacturing hubs dotted along the East Coast.

“Modelling physical damage is easy, but business interruption is much more challenging as complex supply chains can stretch across multiple sites and global markets,” says Andrew Tait, senior consultant, practice leader at JLT Specialty USA. “Soon inventories will start running out and companies will realise which raw materials they need that they never knew came from Puerto Rico or Houston.”

While supply chain risk management improved following 2005’s hurricanes Katrina, Rita and Wilma, Sherman believes recent benign hurricane activity has caused some firms to rest on their laurels.

“People have short memories. Even some of the companies that implemented really robust risk management programmes post-Katrina have become a little lax in updating their processes,” she says.

According to Tait, many companies have cut supply chain risk management budgets and decentralised functions, and may now be counting the cost. “Unfortunately, many risk managers think their job is to just place insurance rather than facilitating risk management. Once a storm hits, it’s too late for them to do anything other than make sure the claims are filed properly,” he says.

Companies susceptible to windstorm-related disruption in Europe, he warns, should use the lessons from disruption in the US as an opportunity to revisit their own exposures and plans to avoid being caught unprepared.

Risk mitigation

According to Katz, getting full visibility into the global supply chain and implementing robust business continuity plans, such as finding alternative suppliers or stockpiling key components, gives any company a big competitive advantage.

The first step, he says, is to evaluate which products and services are most valuable to the company (either in margin or growth potential, for example), then to assess the financial impact if a supplier fails to provide materials that support those products.

A key supplier is one that provides an essential good or component, particularly if that product is a one-of-a-kind or of demonstrably higher quality than the available alternatives. Many companies are also heavily reliant on key single customers.

“If you have a single source or sole supplier, those warrant most scrutiny in terms of impact, particularly when they support a valuable product,” Katz says.

“Ask your primary suppliers how they manage their supply chains and if you’re not comfortable with the answer, dig further,” Katz adds. “Assume that first tier suppliers will manage supply chain risk on a second-tier basis on your behalf at your peril.”

Former RIMS president Rick Roberts, now director of risk management and employee benefits at Ensign-Bickford Industries, says gathering information on risks that exist beyond the primary layer of suppliers can be challenging as not all suppliers are willing to share details of their own supply chains.

Tait advises risk managers to follow Roberts’ lead and partner with colleagues in the procurement and supply chain departments of their own organisations to curate as comprehensive a record of suppliers as possible. He suggests paying for this out of the risk and insurance budget to incentives those departments to participate.

“We do a lot of work through our sourcing departments to assess our key suppliers, see where they are located and to make sure they have good business continuity plans in place, so we know that if they are knocked out we can go elsewhere,” says Roberts. “We try to extend that out to every primary supplier.”

Global insurers and brokers can also help connect dots within the supply chain using their own client lists. After all, it is in their interests to reduce risk aggregation in any given industry sector.

“One mistake companies often make is to pass a list of suppliers to insurers based on the headquarter addresses they see on their bills rather than the actual locations the products are coming from,” warns Tait. “We saw a lot of this in the wake of the Thailand floods Fukushima event.”

Towers Watson estimated that as few as 3% of businesses had contingent business interruption (CBI) cover when Katrina hit. With supply chain risk a growing concern for many businesses (see box), the uptake of CBI has undoubtedly increased since then, though it is no silver bullet, with most carriers limiting cover to the primary layer of suppliers.

There is no doubt, however, that insurance is an essential last line of defence against catastrophic weather disruption. “Your balance sheet can withstand a relatively small event but probably not the whole Commonwealth of Puerto Rico being offline for six to 12 months if you rely on infrastructure and services,” says Tait.

Modelling exposures

He recommends companies model the impact of various storm types, from 100-year to 10,000-year events, establishing what insurance costs at each increment. “You may decide not to buy insurance for the 100-year event any more, but make sure you’re covered for the 500-10,000-year storms or quakes,” he says.

Not everyone is sold on these metrics. “We’ve only got less than 100 years of storm data, so when people say a storm is a 500-year storm, we don’t know that for sure. These things could occur a lot more frequently than we think,” says Roberts.

Roberts agrees that improvements in hurricane modelling, forecasting and tracking have improved risk managers’ ability to map supply chain threats and make more informed decisions quicker than ever before, though he feels not everyone is taking advantage.

“It gets me how little credence people put in the University of Colorado’s hurricane projections,” he says. “They were spot on this year, but I didn’t hear risk managers saying, ’we’ve got to be ready for these hurricanes that are coming’. It was too late when the first two made landfall.”

Technology can now also help companies assess, quantify and stress test the risk within their supply chains, with several carriers, brokers and insurtech firms offering proprietary software tools. Adapt Ready, for example, uses machine learning/artificial intelligence to identify risk interconnections and accumulations within global supply chains.

CEO Shruthi Rao claims that as well as helping risk managers build resilience, this technology also significantly accelerates the claims process. “A business interruption claim typically takes over 100 days to reach the insurer, according to Allianz research. Our risk intelligence platform can bring this down to as little as 24 hours.”

Tait suggests that clients with more than five to ten sites employ some form of analytic modelling, revisiting these models every few years, or at least upon significant changes to the company, such as M&A activity.

As Sherman points out: “A company is never static, so what worked for you last year or the year before, might not be right for this year’s hurricane.

“With Harvey, no-one anticipated that much rain could fall on Houston, ever. Even for the most well-prepared companies, which are in the minority, there was still lot to be learned.”

——————-

Mitigating weather-related supply chain risk

- · Map comprehensive matrix of entire supply chain

- · Identify most valuable products and critical suppliers

- · Ensure supplier details refer to production facilities not headquarters

- · Overlay flood/hurricane/natural catastrophe maps to identify exposures

- · Stress test financial impact from various supply shortages

- · Develop business continuity plan (including finding alternative suppliers)

- · Consider stock-piling key supplies ahead of hurricane season

- · Regularly check weather modelling sites for forecasts

- · Ensure exposed suppliers have own continuity plans and insurance

- · Buy contingent business interruption insurance

——————–

Nat-cat business interruption concerns rising

The Allianz Risk Barometer 2017 ranks natural catastrophes as one of its top ten global business risks, and responsible for $175bn in economic losses in 2016. The top risk was business interruption, with 43% of respondents citing natural catastrophes as the cause of interruption they feared most (second only to fire/explosion).

These findings were echoed in the 2017 Travelers Business Risk Index, which found more businesses worrying about supply chain risks (28% in 2017, compared with 23% in 2016) with severe weather events the most worrisome cause of interruption, particularly among small companies.

According to Travelers, 31% of companies have their primary supplier located in an area prone to severe weather, natural catastrophe or political conflict; 49% rely on a single supplier for more than 25% of their materials; and 52% admit they may not have a backup inventory plan.

No comments yet